Your donation will support the student journalists of Iowa City High School. For 2023, we are trying to update our video and photo studio, purchase new cameras and attend journalism conferences.

Boys and Girls and Everything In Between

Three City High students share what it’s like on opposite ends of the “gender spectrum.”

February 9, 2016

A 2012 survey by the Equality and Human Rights Commission found that around one percent of the U.S. population identifies as “gender variant” to some degree. For this one percent of individuals, gender may be better represented as a spectrum rather than the a baby pink or sky blue, or they may find that their gender as listed at birth isn’t entirely representative of their identity.

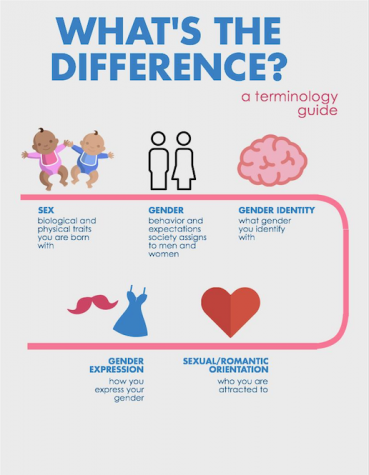

A guide to the difference between sex, gender, gender identity, gender expression, and sexual/romantic orientation.

Over the past decade, information about nontraditional gender identities has become more readily available due to the rise of the Internet. Ours is among the first generations to be able to connect via the World Wide Web, which has helped to spread an understanding of what it means to identify as something other than “male” or “female.” Now, people are able to research their feelings of gender dysphoria (the feeling that a person’s body does not match their true identity, which some transgender people experience) and determine how they are best represented. Alex Pradarelli ‘18 is one of these people.

“I didn’t really want to tell anybody until I was certain,” Pradarelli said. “I was researching it for a while, trying to decide if this was really something I wanted to do, because I didn’t want to be uncertain about it and have it be this long process where everyone was asking me questions.”

Named Abby at birth, Pradarelli knew from a young age that he didn’t identify with the traditional female stereotypes. He came out as gay in the fifth grade, but somehow that still didn’t feel like the complete truth.

“You know when you say you’re straight and you just know that’s who you are? When I came out as gay, it was still uncomfortable. Once you finally figure that out about yourself, you should feel good, like, ‘Okay, I figured out who I am,’ but that wasn’t how I felt, necessarily,” Pradarelli said. “It felt like there was more to it, and that’s what I was confused about and trying to understand.”

Pradarelli researched gender transitioning for over a year before deciding to tell his parents.

“My whole family is pretty okay with all this kind of stuff,” Pradarelli said. “I knew my parents would support me, but there’s always that fear of telling them, because it’s like, ‘I don’t want to be wrong,’ but at the same time you know yourself, so you’re obviously not going to be wrong.”

With the support of his family, Pradarelli started taking testosterone this past October, and plans to have top surgery within the next two months.

“It’s different for everyone. Everyone has their own journey, or what it means to them, because some trans people don’t take hormones and don’t have surgeries, and they’re okay with that, but they still identify as the other gender,” Pradarelli said.

Gender identity is a person’s internal sense of whether they’re male or female or somewhere in between. Facebook’s new profile format, with over 50 gender options, demonstrates just how vast the gender spectrum is. However, gender identity is not synonymous with gender expression. Gender expression is defined as the way a person communicates their gender identity to other people. The most common modes of expression are through clothing, hairstyles, speech, and body movements. For example, Pradarelli expresses his gender through a coiffed pompadour, button-down shirts, and men’s jeans.

While Pradarelli identifies more as a male, Liana Gabaldon ‘16 identifies as neither male nor female, and prefers ‘they’ as a pronoun.

“I knew that I wasn’t feeling like a girl, but I knew that I wasn’t completely on the opposite side; I knew I wasn’t a guy,” Liana Gabaldon ’16 said. “I wondered what other things were out out there, because I knew there were more than just the two extremes.”

“I identify as genderqueer,” Gabaldon said. “So constantly fluctuating feelings of gender, and where I land on the spectrum.”

Gabaldon began to confront their identity around sophomore year, and like Pradarelli, they did so by researching on the Internet.

“I knew that I wasn’t feeling like a girl, but I knew that I wasn’t completely on the opposite side; I knew I wasn’t a guy,” Gabaldon said. “I wondered what other things were out out there, because I knew there were more than just the two extremes.”

Like Gabaldon, Charlie Escorcia ‘18 doesn’t identify as either male or female, but he places himself somewhere in the middle.

“I’m non-binary,” Escorcia said. “I go by the name Charlie, because it’s just more neutral, but I’m also okay with masculine pronouns, like he and him. I don’t dress super feminine, but I don’t dress very masculine either. I just wear jeans and a t-shirt, very neutral. I guess I go very neutral sometimes because I’ve had people ask if I’m a boy or a girl and I’m like, ‘I don’t know.’”

Escorcia started to wonder about his identity a couple years ago, and only landed on non-binarism after extensive research on gender identity.

“I was really confused, when I was questioning my gender, because I didn’t feel like a boy, but I didn’t feel like a girl,” Escorcia said. “I was like, ‘Ay, non-binary gender is a thing, so maybe that’s me.’”

Charlie Escorcia ‘18 doesn’t identify as either male or female, but he places himself somewhere in the middle.

Like Pradarelli, Escorcia received support from his family as well as a network of friends in the LGBTQ+ community. City High psychology teacher Jane Green noted the importance of familial support and accepting communities, such as Iowa City.

“All teens have to come to terms with their identity, everybody goes through it. But this is a little bit increased because it’s not the norm. It doesn’t fit all of society’s rules, and society’s acceptance is hard to get,” Green said. “I think it depends a lot on the family: Is the family accepting or not? If the family is accepting, to what extent? It depends on each individual situation.”

However, familial support isn’t all that common for many. One survey concluded that 57 percent of transgender and gender nonconforming individuals are rejected by their family. Because so many experience this kind of rejection, many members of the LGBTQ+ community must turn to their community for support.

“We’re lucky to live in Iowa City,” Green said. “I could think of half a dozen places in Iowa I wouldn’t want to live. It would be possibly unsafe. We’re in this insulated, educated area and yet, you’d be surprised at how many people really don’t know about gender identity, gender expression.”

Green believes education is the key to more widespread understanding and acceptance of transgender and non-binarism.

“I do think our society is getting much more accepting on a lot of different levels. It’s just going to take some education. People are afraid of what they don’t know and they need to experience it. They have to be around these folks and realize that they’re just people,” Green said.

Slowly but surely, this acceptance is becoming more common. Celebrities like Laverne Cox, Caitlyn Jenner, and Ruby Rose have helped start a discussion in our culture about transgenderism and gender fluidity. From Netflix’s hit show “Orange is the New Black” to the recently released movie “The Danish Girl,” more LGBTQ+ are being portrayed in popular culture. This signals an overall increase in acceptance, especially with younger generations. The number of Americans who identify as gender variant is around three million, a number that Green credits to the newfound understanding and the accessibility of the Internet.

There are hundreds of possible gender identities. Gender identity is a person’s perception of oneself as male or female, both, or neither. This is manifested in how someone presents themselves to society.

“If you compare today with 20, 30, 40 years ago, there were still people who felt this way, but they didn’t feel like they could come forward or change anything in their lives. So they were very unhappy and depressed throughout their whole lives,” Green said. “We’re seeing kids today realize things at a much earlier age and say, ‘That’s not what I want. That’s not who I am.’ And having people say, ‘Okay.’ Including school districts. That never would have happened 20 years ago.”

Even so, Pradarelli, Escorcia, and Gabaldon all agree that the concept of the traditional gender binary is heavily ingrained in our society, and that anything beyond that is often difficult for people accept. In fact, until 2012, gender dysphoria was known as “gender identity disorder,” or GID, and was classified as a mental illness.

“They were talking about GID being a problem instead of it causing other problems, like depression and anxiety,” Green said. “And now we know the difference. There’s treatment for depression and those kind of things, but for GID, people are who they are. So the treatment is acceptance.”

This treatment, however, can be difficult to come by. The average individual is especially unfamiliar with gender identity that goes beyond male or female—which is in some ways a result of a system where male/female are the only two options on many legal documents and public spaces.

“It’s such a strange issue and concept to people, and they don’t want to go outside the realm of the little normal they’ve built for themselves,” Gabaldon said. “But being outside gender binary is completely normal. It’s just not their normal, so it makes them uncomfortable.”

For Pradarelli, the difficulty lies in understanding. Though people have struggled with their identity throughout history, “non-binary” isn’t a title that has been widely used until fairly recently.

“That’s uncomfortable to them because they don’t understand it,” Pradarelli said. “There’s either male or female and you’re born that way and that’s how it is, and I think it’s hard for people to understand that that’s not always the case for people.” — Pradarelli

Indeed, the idea is frequently ridiculed, especially on the Internet. Genderqueer, non-binary, and gender-fluid individuals are often accused of simply desiring attention over anything else. One Reddit user, _trashpanda_, wrote, “99.999% of people who claim to be ‘genderqueer’ are, in reality, historic attention whores.”

“People get hostile because they don’t understand it,” Pradarelli said. “There’s boys, and there’s girls, and anybody in between messes that up, and that scares people in a way.”

Gender neutral bathrooms are another issue where opinions are sharply divided. In 2013, Arizona passed Senate Bill 1045, which protects business owners from criminal liability if they choose to ban someone for using a bathroom that doesn’t match their sex at birth. Talk of a gender neutral bathroom has recently surfaced at City High, though there are no official plans for construction yet.

“I’m more comfortable with using the women’s bathroom, because that’s what I grew up with and I don’t have a problem with it,” Escorcia said. “But sometimes, when I’m dressed more masculine, I’m worried that people will react to me being there– either because they know I’m passing as a male or they’ll harass me about looking like a guy and being a girl.”

Bathrooms are a classic example of gender binary in American society—which, in an image, is the stick figure versus the stick figure in a dress. For many, however, the simple task of using the restroom becomes stressful when they have to choose.

“When I’m at the mall or at a restaurant, it’s kind of scary,” Pradarelli said. “I’ve been trying to go into the guy’s bathroom, but it’s kind of like, ‘Where do I go?’ A lot of times I just don’t go to the bathroom until I get home.”

Escorcia and Pradarelli believe that a gender-neutral bathroom would be a step in the right direction towards an even more accepting environment at City High. The University of Iowa’s Memorial Union building has had a gender neutral bathroom since 2013, following an overall progressive trend among college campuses. According to a study by the University of Massachusetts LGBT organization, there are over 150 college campuses now offering a gender neutral bathroom to their students.

“I definitely feel that non-gender bathrooms are definitely helpful, because it’s not that awkward thing where everybody’s looking at you weird, or questioning you,” Pradarelli said.

Gabaldon, Pradarelli, and Escorcia all agree that Iowa City is a very open and tolerant town, and somewhat unique in a society that still struggles to talk about issues pertaining to the LGBTQ+ community. While they can’t help but wonder about how the rest of the world will accept them, they are confident that they will find a welcoming community.

“I feel like if I do leave, there’s definitely the possibility of people not accepting me,” Gabaldon said. “But I do also think that I will be able to find people who do accept me, and just thinking about that is important, and remembering that there will always be someone, somewhere, and I’ll always have someone supporting me.”