Your donation will support the student journalists of Iowa City High School. For 2023, we are trying to update our video and photo studio, purchase new cameras and attend journalism conferences.

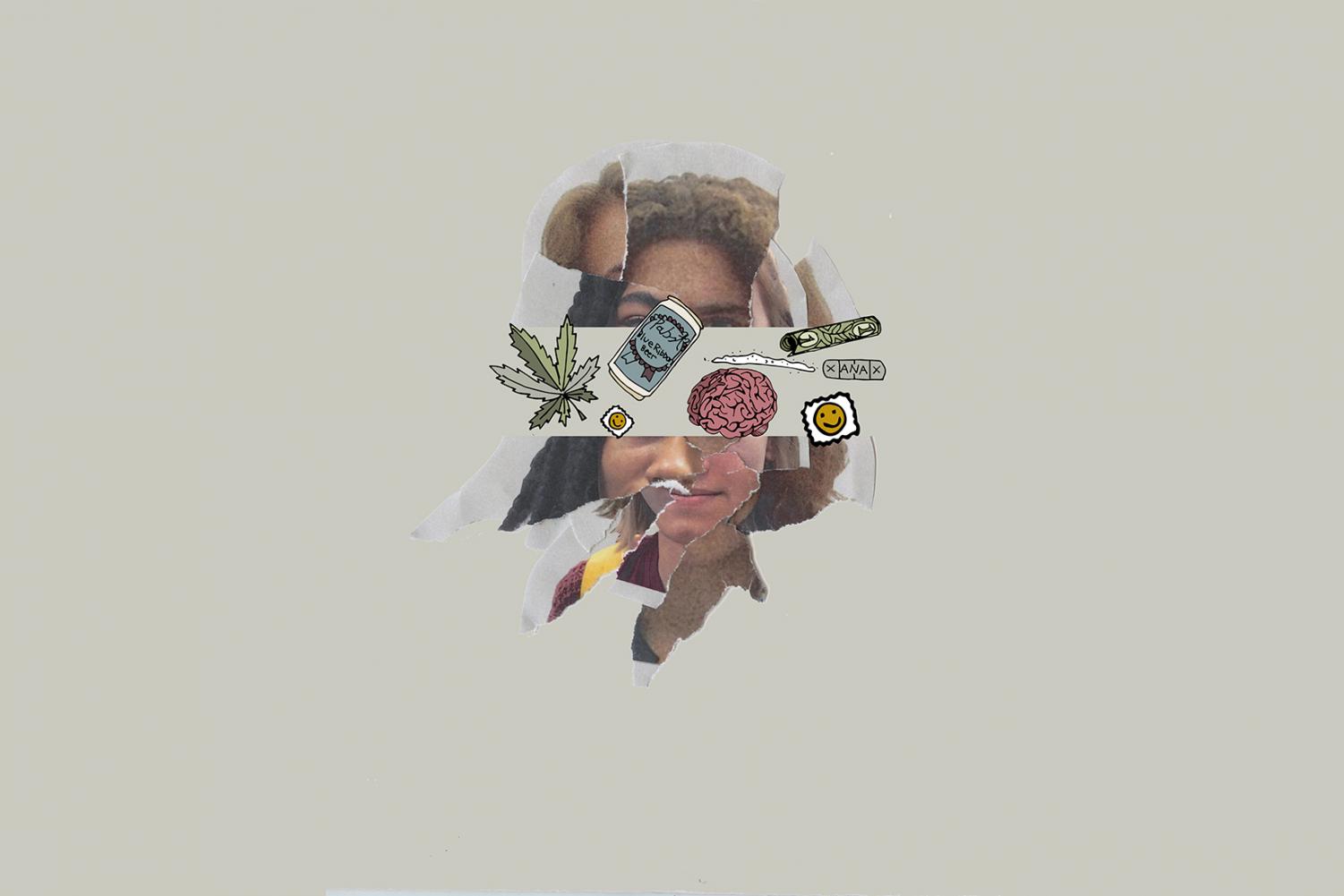

For the Thrill of It

October 31, 2018

For Violet*, it started in fifth grade. She and a friend were together on a snow day, and her friend suggested they try smoking marijuana.

“I was like, “Oh, [smoking’s] cool. I’m going to do it too,” she said. “We just said, ‘f*** it, we’re going to smoke.’”

The National Council On Alcoholism And Drug Dependence, or NCADD, says the most prevalent characteristic of substance users is a history of family use—the offspring of addicts are eight times more likely to develop a dependence on a substance. However, Violet didn’t grow up in such telltale circumstances; her parents have never taken any drugs or abuse alcohol.

“My parents barely even drink or anything, they don’t smoke cigarettes, and my mom only drinks wine, so [substances] were never in my house,” she said. And she was aware of the health consequences of marijuana and other drugs.

According to the National Institute for Drug Abuse, approximately 24.6 million American teenagers have used illicit drugs in their lives. This is due to a multitude of factors, but boils down to one key component—their brains. Similar to other teenagers, Violet has an undeveloped frontal lobe and prefrontal cortex, areas of the brain that affect self-control and decision-making. According to Dr. Laurence Steinberg, a professor of psychology at Temple University, this can lead to teenagers making riskier decisions than an adult might.

“The brain’s self-control system is immature in childhood, but at puberty there is an increase in sensation seeking and reward seeking, which makes teenagers act in ways that they don’t yet have the maturity to easily control,” said Dr. Steinberg.

Violet was no exception to this phenomenon. As she began high school, her previous experimental forays into marijuana shifted to usage of prescription drugs such as Xanax (alprazolam), Oxycontin, and Hydrocodone. She began taking larger quantities of the pills, especially Xanax. During this time, the dosage of Xanax she was taking became a complete afterthought.

“I was taking a lot of Xanax, so I was just off so many Xans all the time that I have no recollection of like three or four months of [sophomore] year,” Violet said. “I didn’t care about dosage at all, I’d take seven [two-three milligram] Xans.” By her account, Violet would have taken 14 milligrams of the drug — almost four times the typical prescribed daily dosage, according to drugs.com, an online prescription drug database.

Violet says she felt “like a zombie” during her the period of her high usage of Xanax, and began seeing the signs of her addiction with her family and schoolwork. I was just off so many Xans all the time that I have almost no recollection of like three or four months of [sophomore] year. — Violet

“[Xanax] was really taking down my grades. I had a really bad GPA and I eventually was expelled because I was truant, because I just wouldn’t care and not go to school,” Violet said. “I wasn’t really talking to my mom or dad that much, and I was just caring about the people that I hung out with that provided me with the Xanax.”

Violet has tapered her drug usage, and stays away from all pills now. However, during the three to four months she was addicted to Xanax, Violet was a survivor of multiple instances of sexual assault by some of her closest friends at the time. The first time, Violet was attacked while on Xanax. The second time, her friend told her she was taking a liquid form of Xanax. It was actually Rohypnol, a common date-rape drug.

“I have PTSD and stuff, so it’s definitely changed me in a negative way,” Violet said. “But also a positive way, because I learned a lot from it.”

PTSD and other trauma disorders are not uncommon for adolescent drug users. According to a study conducted in part by Dr. Jennifer L. McCauley, an assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the Medical University of South Carolina, 11.8 percent of teenage girls experience sexual assault; one-fifth of those assaults are while the victim is under the influence of a substance. Of the girls who experienced assault, those who were incapacitated had a “significantly larger chance” of reporting symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

The effects of high risk behaviors—specifically substance abuse—reach far beyond the individual who engages in high-risk behaviors, too. Friends of adolescents who take lots of risks face serious emotional changes from observing their friends.

This is the case for Gray*, another student. Gray’s friend group smokes a lot of marijuana, but he himself stays away from all drugs and alcohol. He believes his friends do drugs for a simple reason: they enjoy them.

“It’s a little not fun for me. Everyone’s obsessed with the notion of never being sober. Nobody ever wants to be sober, and it has an effect,” he said. “It’s really hard to deal with. I’m never going to have a time where everyone is willing to just be themselves and not on anything.”

According to a study by Julia Shadur, Ph.D. and Andrea Hussong, Ph.D., adolescent drug use and abuse can have detrimental effects on interpersonal relationships. They found that “at low levels of close-friend substance use, adolescents with the lowest levels of close-friend intimacy are also more likely to use substances compared to those with high levels of close-friend intimacy.” Adolescents are more likely to use drugs when they feel a lack of connection to others.

Gray has witnessed his friends on a wide range of substances—from psychedelics to opioids—and said the more he he sees and experiences, the less he understands why his friends use drugs or engage in high risk behaviors.

“Being around [my friends doing drugs] makes me understand it a lot less, too. I understand it to a point—it makes you feel really good about yourself. But there are so many repercussions and nobody considers those or takes them into account. I think [my friends] just view it as a way to have a good time, and that’s not always what it is,” Gray said. “They take [MDMA] and they have a good time and then they’re messed up. They’re depressed for weeks. Is it really worth being happy for a few hours and then absolutely hating yourself for a month? Is it worth it? I don’t think it is.” It’s really hard to deal with. I’m never going to have a time where everyone is willing to be themselves and not on anything. — Gray

According to dancesafe.org, an organization which promotes safety with psychedelics and other aspects of nightlife, MDMA drastically increases serotonin, a neurotransmitter which contributes to feelings of happiness; on users’ “comedowns” they experience a depletion of serotonin, which leads to feelings of depression.

Gray’s friends’ issues with drugs are not solely limited to their despondent mental states post-usage; they can seep into more tangible real-life consequences. For example, his friends often decide to drive drunk home from parties.

“They think it’s okay to drunk drive. And it’s not like it’s once in a while—at every single party there are like four or five people who drunk drive,” he said.

In one instance, Gray, along with a few friends, unknowingly got a ride home from someone who was tripping on LSD.

“He had no idea where he was, even though he’d driven that route a few times. He was convinced we were aliens who were trying to hurt him, that we weren’t his real friends and that we were trying to mess with him in some way,” Gray said. “He forgot where he was a few times, we had to direct him the whole time. He stopped at a green light and got out and just started looking around. It was terrifying.”

According to Dr. Steinberg, this kind of behavior has a lot to do with peer influence. Decisions to drive drunk, use drugs, or engage in other risky behaviors have close ties to what ones’ friends and peers do and say and a desire to fit in.

“I think most teenagers are inclined to take risks, and the big difference among them is in how the risk-taking is manifested,” he said. “That’s where parents and peers are important as influences and role models.”

Violet found this to be the case for her, too.

“Yeah, [what I’ve done] was entirely peer pressure,” she said. “I have social anxiety and stuff, so it was a lot of me trying to fit in and make friends, so I would just do what everyone else was doing in my friend group.”

Violet has gotten back on track with her dream of majoring in computer science at the University of Iowa, even after her period of high usage.

“Just because I messed up last year it hasn’t affected me much as a whole,” she said. “I’ve always been a pretty smart kid — my freshman year I had a 3.85 GPA, and it’s the same this year now that I’ve tried hard again in school.”

On the contrary, some of her friends are stuck in the same cycle she was lodged in.

“I’m definitely still able to do what I want to do and be successful. They think they’ll make more money selling drugs, so they don’t really care about going to school.”

Dr. Steinberg believes, though, that not all risk-taking is inherently negative.

“It’s important to remember that there is a lot of positive risk-taking that likely has psychological benefits,” he said. “Trying out for a team one doesn’t expect to make, performing in a play in front of classmates, approaching someone you have a crush on and are nervous about talking to, taking classes that don’t guarantee good grades, etc.”

Risk taking has pros and cons, and is inherent in growing as a person. It is what you deem as truly important which affects the direction of your future.