#StopAsianHate Movement Battles Rise in Hate Crimes

The U.S sees a rise in anti-Asian hate crimes across the nation resulting in the rise of the #StopAsianHate Movement

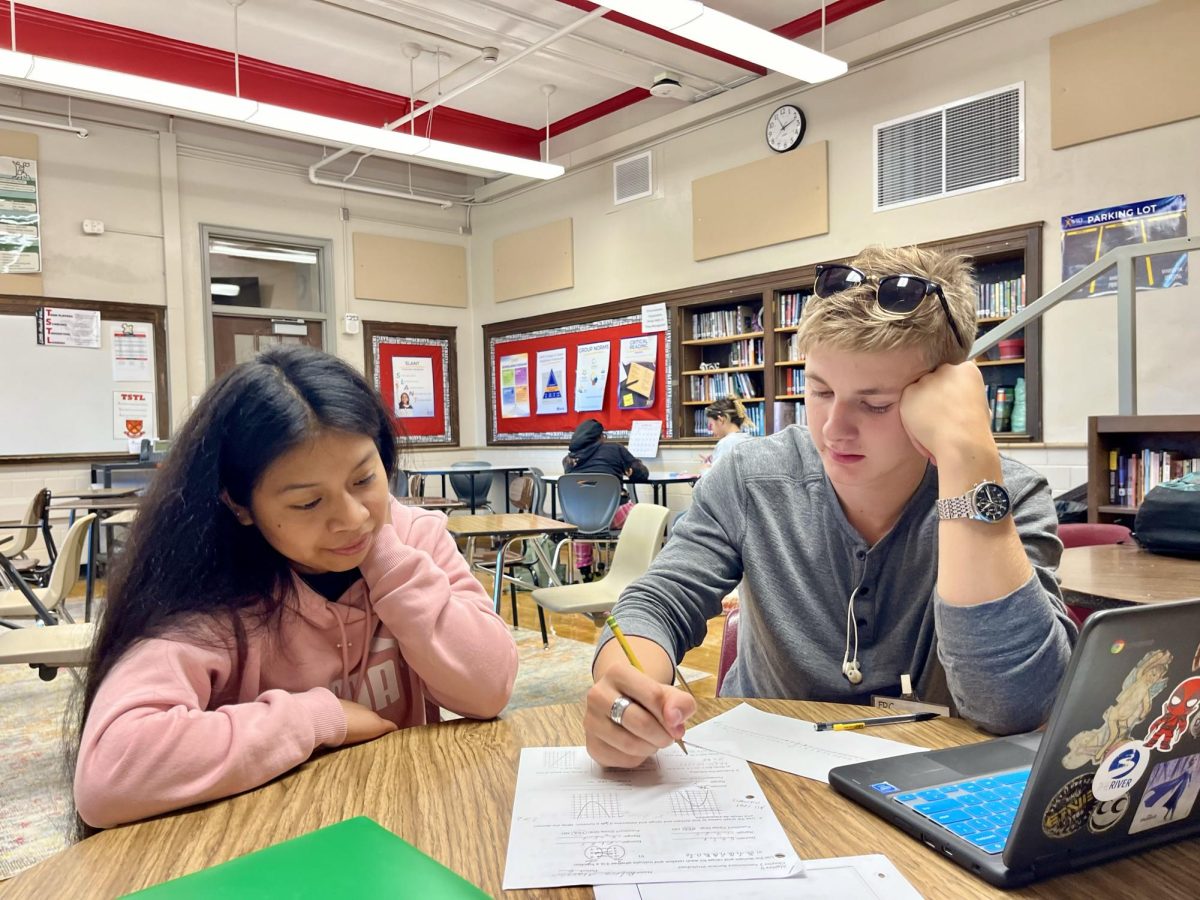

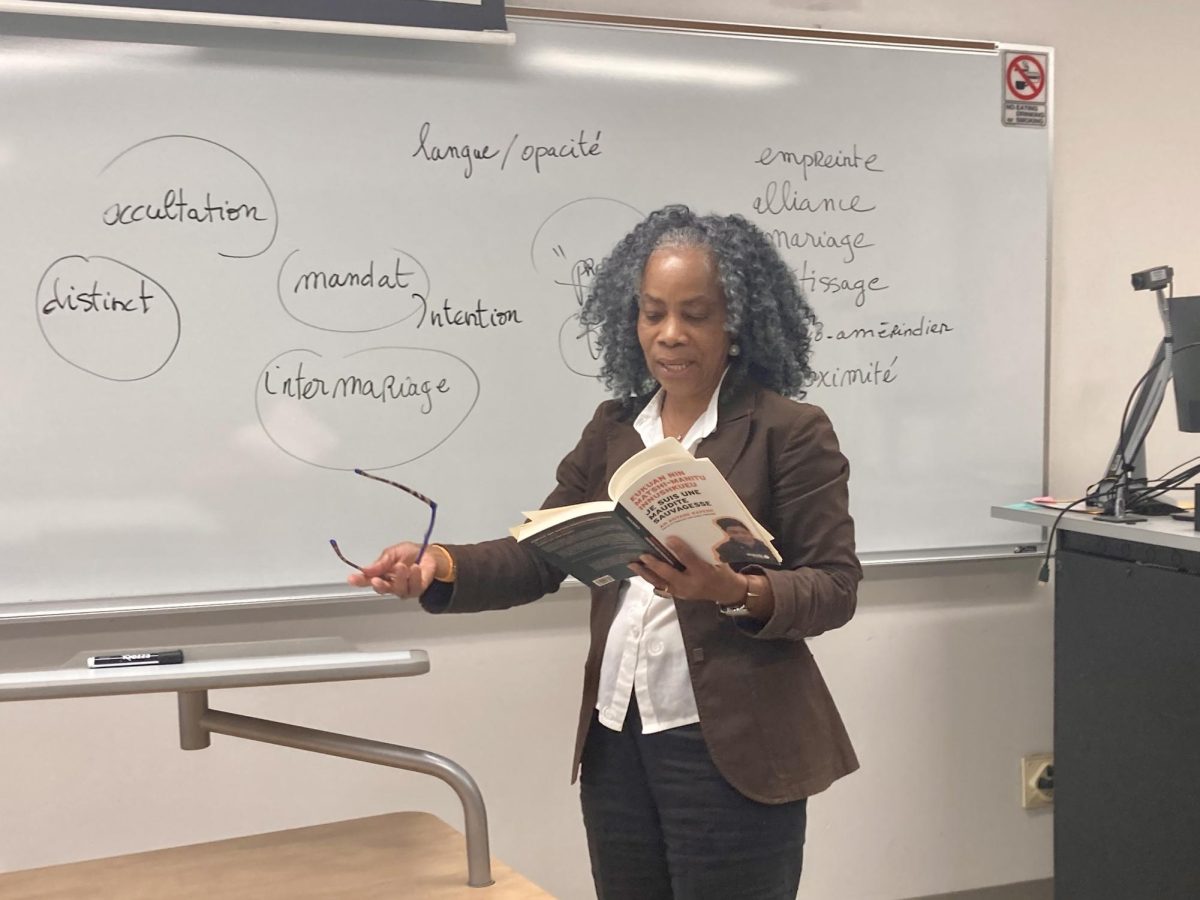

Photo of Thomazin Jury and her Filipino family members

Melanie Tran Duong ‘21’s father came to Iowa City decades ago after fleeing the Vietnam War. Though he was supposed to go to City High, he instead had to attend West High because it was the only school that had an English language learning program. Other members of Tran Duong’s family, such as cousins, attended City High later.

“They definitely faced a lot of microaggressions and just aggressions in general. My cousins got into fights all the time because of it. I think because of COVID and just talking about it with my cousins, I got a lot closer to them. I learned more about what they went through,” Tran Duong said.

In recent months, the surge of anti-Asian hate crimes and racism across the U.S has caused an uproar within the Asian community and its allies. The topic has gained much traction and has resulted in the #StopAsianHate and #StopAAPIHate movements being shared across social media.

“It’s really hard to talk about with friends that aren’t Asian, so they don’t understand where you’re coming from with your struggles with just trying to deal with it,” Tran Duong said.

One recent act of violence was a series of shootings that took place on March 16 in Atlanta, Georgia. The attacks targeted spas in the Atlanta area and killed eight people, six of whom were Asian women.

“It made me sad to think that it just started to become a trend to start supporting [Stop AAPI Hate] when it’s been such a long history of these crimes since the California gold rush and then the yellow fever,” Thomazin Jury ‘21, who is half Filipino, said. “When the mass shootings happened, my family and I were actually in Georgia at the time and we were planning to go to Atlanta the next day. But then we just decided to cancel that trip because we honestly didn’t feel safe to go. That was really a lot, and it just was scary.”

The Stop AAPI Hate Reporting Center, a nonprofit social organization that tracks incidents involving discrimination, hate, and xenophobia towards Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the U.S, stated in a recent report that an estimated 3,795 hate incidents were reported to their center between March 19, 2020, and February 28, 2021.

“City High is a very diverse population and Asian Americans are probably on the much lower end of that,” Oliver Bostion ‘21, a half Korean student, said.

These hate incidents have involved verbal harassment, shunning, avoidance of Asian Americans, physical assault, and online harassment, along with a mass amount of hate targeted specifically toward elderly Asian women, according to the Stop AAPI Hate National Report.

“My grandpa, he’s like 95 and he loves to go on walks. But he goes on walks by himself, and that’s really scary, so we told him not to do that anymore,” Tran Duong said.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also resulted in a surge of anti-Asian hate crimes. According to Pew Research Center, 31% of Asian Americans reported having experienced incidents of racial slurs and racist jokes since the beginning of the pandemic.

“It’s been really shocking and just really disheartening, especially knowing that a lot of members of my family are very elderly that are just living on their own out in a different part of the other side of the country. It’s scary to think that I can’t be there to help them or console them,” Jury said.

Throughout the pandemic, former President Donald Trump referred to the COVID-19 pandemic as the “kung-flu” and “China virus” in relation to the virus originating from Wuhan China.

“The whole issue with Coronavirus being called the ‘China virus’ is people telling specifically Asian Americans, and actually any minority, to ‘go back to your own country and to ‘get out of here.’ It is such a flawed way of thinking, especially knowing that the U.S is made up of immigrants, so it’s a really unfortunate thing that people of color have to face,” Jury said.

Many Asian American advocates feel that former President Trump’s words provoked an anti-Asian sentiment in the U.S and could be linked to the recent increase in violence against Asian Americans.

“That’s textbook ignorance when Trump was talking about the ‘China virus’, so anyone who looks like they come from China must certainly be carrying [the virus]. I think that’s obviously horrible. There were a couple of times when I felt like people were maybe looking at me funny,” Bostion said.

However, COVID-19 isn’t the only motive for anti-Asian hate in the U.S. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, the only piece of legislation implemented in the U.S specifically banning all members of a certain ethnicity or nationality from entering the nation. During World War II, not only were all people of Japanese descent put into internment camps but there was a national rise in anti-Asian sentiment, regardless of country of origin.

“I feel like it stems from people being ignorant and not being able to accept other people for their differences, and not educating themselves on what is actually occurring and how it would actually affect other people besides themselves,” Tran Duong said.

In 1992, Los Angeles erupted in riots following the acquittal of four police officers who beat a Black man named Rodney King. The acquittal was the fuse for tension that had already been building, as a Korean store owner had shot and killed a black girl earlier that year. The main targets of the riots were Korean Americans living in L.A. who had their homes and businesses looted and burned down.

“[The violence is] scary to me, especially since my grandparents both have pretty heavy accents. I think that definitely contributes. I’m not an expert, but I would think that they would be more likely to be victim to something like that because they’re older and they don’t speak perfect English,” Bostion said. “I would be worried for them in places where maybe people are less educated and they haven’t been exposed to as many people who [don’t] look like them.”

Jury hasn’t experienced any violence due to her ethnicity, though she has experienced certain microaggressions such as type casting in theatre, the profession she wants to go into.

“Most of the roles I was given when I was younger were supposedly kids of color or only Asian characters. I’d be typecast as someone who’s really quiet, timid, and smart which is a common stereotype for Asian women,” Jury said. “Even when I’d go to a program to get training from people, I would only be recommended songs that are sung by Asian women. I was told in a class that, ‘Oh, well you’re Asian, you’d like this little product because they’ll think that you’re smart, so it’ll all work out,’ and nobody said anything to me after that. People laughed and that was it.”

While Jury has felt typecast into the “model minority myth” in theatre, other Asian American students have felt “typecast” into this role in their real lives.

“I feel like I’ve definitely had different experiences, because it kind of ties in with the model minority myth where people expect a lot out of me,” Tran Duong said. “And so I match those expectations, but then those expectations are put on other people. I’m living the model minority myth. I feel like a lot of children in my generation, they want to live up to that. I think that [parents] pressure their kids to try to live up to that when there shouldn’t be any pressure at all and everyone should be given the same.”

While Tran Duong feels that she excels in school, she believes that there is an added pressure from those around her due to their perception of her based on her ethnicity.

“I definitely feel like if I didn’t do as well in school as I do now, my teachers would look at me completely differently,” Tran Duong said. “I feel like they would be like, ‘Oh, why isn’t she excelling in school,’ because I feel like people have those stereotypes and they will always be there.”

The model minority myth is the idea that Asian Americans are supposed to be the most successful minority group in the U.S. According to NPR, many cite that this stereotype is used to drive a wedge between different racial minority groups.

“I think [the model minority myth] makes [Asian Americans] feel like their experiences aren’t valid enough,” Jury said. “If something happens to them I think they’re afraid of being seen as weak or as not being able to take care of themselves because, for the longest time, Asian Americans have had to provide for themselves and work their way up to even be seen as people in America. I do think it’s that fear that holds them back from wanting to speak out because they’re afraid to.”

Jury hopes that people will continue to take action against racism against Asian Americans, beyond merely the hashtag #StopAsianHate.

“I’m glad to see that there are people out there that are genuinely wanting to spread awareness about this because it has been going on for way too long and it’s unfortunate that it’s just now being talked about,” Jury said. “It’s a small step that I think that has benefited a lot of people and will make people more aware if they see something on the street or maybe within their friend group or at school. Overall I think it’s a positive thing, but it’s just a small step.”

She hopes that people will continue to support Asian Americans in other ways.

“I think the best thing you could do is to really listen to people’s stories and experiences, to spread awareness, to stick up for people of color, and support local businesses. If you really love Asian culture, then you should really show your appreciation for Asian people as well,” Jury said.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Iowa City High School. For 2023, we are trying to update our video and photo studio, purchase new cameras and attend journalism conferences.

Shoshie Hemley is one of the news editors. She has a lot of opinions. She has a lot of strong feelings about a lot of things. Come talk to her to have...