The Review Revived

The Review facilitates future projects to reimagine publication into an interdisciplinary student-run program that fosters artist community and supports student mental health

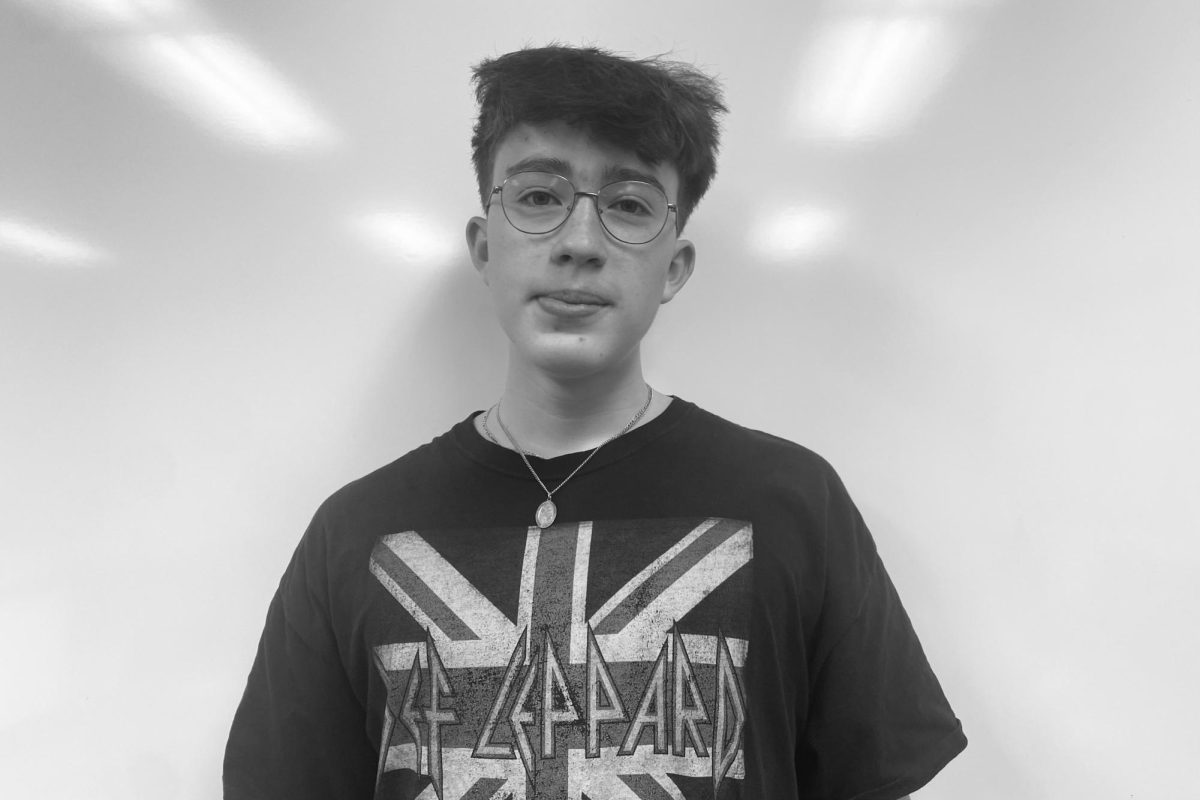

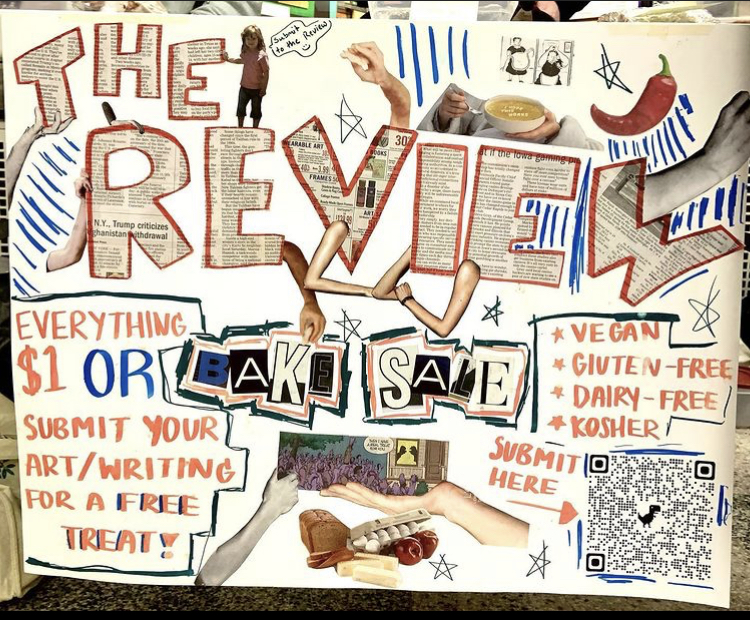

Review staff members make poster for bake sale.

December 16, 2021

Taking her seat in astonishment, executive editor of the Review, Rachel Tornblom ‘22, scans the room as more students file in to take their seats for a Wednesday after-school meeting. Simply put, the Review scouts and publishes art and literary work for their biannual magazine. However, according to the editor, submissions and staff at the Review have faltered for years, hitting an all-time low over the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet that afternoon proved to be the Review’s largest staff turnout yet in two years.

“I wasn’t sure how many interested students would show up at the beginning so it was a little scary starting. For the first few meetings, we had two people show up. That was better than none,” Tornblom said. “Then it took off. I think it was just getting people to come to the meeting once because once they come to the environment and see what it’s about it’s easy to come back.”

According to Tornblom, the club’s activities suffered during the past year due to obstacles presented by the COVID-19 pandemic. Online learning posed an additional level of difficulty when the Review not only scouted for submissions but scouted for new members. As a result, the Review ceased to publish their biannual magazine. Unfortunately, the challenges the Review faced as of last year also trickled down to the current academic year. Almost all staff are new to the club, making organization and prioritization a challenge. However, new staff views this as an opportunity to reimagine the Review’s place at City High for future generations of students.

“Since a lot of people don’t know how we run, it’s given us some freedom to look towards other literary journals and see what new things they are doing,” Tornblom said. “We have a lot of projects happening now that wouldn’t have been possible without the amazing influx of interested students. On top of that, we have been able to reimagine what role this magazine can fill at City since there are very few pre-established traditions.”

Previously, Tornblom recalls a feeling of frustration by lack of staff and awareness of a historically productive publication. According to her, many students were unaware of what literary journals were and equally uninformed about the Review itself. While Tornblom had many creative ideas to increase staff, submissions, and awareness, the editor had little help to initiate them. To overcome this obstacle, Tornblom started a unique method of student recruitment that sparked the revival of her publication.

“I just started asking my friends to ask around and those students started asking around. Once we had started this crazy recruitment web, it was a domino effect,” Tornblom said. “At meetings, we asked new people to either find three art/writing submissions or bring someone new to the club. I think students immediately saw how open to new ideas the club had become, which caused a lot of especially new students to immediately start contributing to group discussions and to feel like they had a place at City High.”

There are two main ways for students to become involved with the Review, Tornblom explains. The first involves submitting student work. This year, the Review will be accepting a broader range of submissions, encompassing art, photography, poetry, short stories, comics, music, podcasts, and comics. Tornblom reports that the magazine is aiming for two print editions, though a third print edition is in question depending on whether the number of submissions remains consistent. While not all submissions end up in the print magazine, Review staff have been working on a website and newly rebranded social media to publish student work in other ways to showcase the talent of students at City High.

“The second way to become involved is to attend Review meetings. Our staff works together in arranging potential events, reviewing submissions, editing literary work, designing print pages, and managing both the website and social media,” Tornblom said. “The Review meets Wednesdays after school. As staff increased, new ideas and projects followed. This year, the Review has created a website, designed a new logo, collected nearly 70 submissions, and raised $900.”

However, one of the biggest project ideas, a student-run programming initiative, has yet to come according to Tornblom. This potential new project idea was sparked when the Review’s programming director Lulu Roarick ’24 first saw the Little Theatre space, a largely unused backup theatre within City High School. Roarick explains that many students do not feel they have a space for themselves, a sentiment reflected during Student Senate discussions. Following her involvement with the Review, Roarick broadened her vision to include student-run projects encompassing the arts as a way to foster community and mental health at City High School.

“I care a lot about students’ voices. It’s something that motivates a lot of my work. When I saw the Little Theatre, I was like, ‘this is a place where students could go. This could be a student-run space.’ And that made me feel very motivated,” Roarick said. “When I went in there it had so much potential. It looked very nice but everything was falling apart. [Resources] such as the video equipment took me 45 minutes to even figure out how any of it worked because it was all scattered about. I think right now, [The Little Theatre] is used for club meetings during advisory. But I think that that space can be utilized more.”

Arts Program Coordinator Lauren Linahon for United Action for Youth (UAY), a non-profit that provides for the welfare of youth in the community, asserts that spaces like these can equip students with tools to navigate the emotional turmoil associated with their age. Linahon’s work practices art education that incorporates social-emotional learning through a culturally responsive lens and a trauma-informed lens. In other words, Linahon is interested in how to use art education to respond to current youth mental health challenges.

“At UAY, we have intervention programs and prevention programs. Prevention programs are things for people to be around like good influences and are there to prevent crises from happening. However, that’s not to say only people in crises should have access to these programs. Prevention programs must be for everybody,” Linahon said. “And our intervention programs are the ones that go in and intervene when a crisis comes up.”

United Action for Youth prevention programs includes art programs, youth center space, a music recording studio, writing clubs, pride groups, music playing room, and many more. Linahon believes art provides a catalyst for self-expression which can be a therapeutic aid.

“Prevention works,” Linahon said. “Giving people a place to come to hang out, to mess around on the guitar, or learn the drums or play the piano. Giving someone space to be themselves and be genuine, to who they are. I think that’s super important. And it helps build confidence for life. So that in itself is prevention work. When someone feels confident about who they are and safe and who they are – that’s prevention.”

Regardless of the type of programming at City High School, Roarick believes that students must set ground rules together to foster trust and open conversation throughout the building. She believes that City High, as with many public schools, lacks the transparency of what rules are and what discipline looks like. According to her, some students are left in an uncomfortable grey area while at school, essentially hindering their potential to start their creative projects. Roarick suspects that not every passionate high schooler has the confidence, support, or the footing to find a sponsor, a space, and a group of students to achieve their vision.

“I think this is something that needs to be done,” Roarick said. “I want students to have a space to foster whatever they’re interested in. [The Little Theatre] has a green screen, it has lights, you can move equipment there. You can do tutoring, you can invite speakers. I think the possibilities are endless.”

In addition to being a medium of self-exploration, art-making can aid in both emotional and cognitive processes, according to Linahon’s research, in two ways. The first is through the physical act of making art or writing. When a person does something with their hands or body, such as writing a poem down or even pacing, information will process at a much deeper level because it will be connected to more than one part of your brain. The second way is through the creativity that creating art or writing fosters.

According to Linahon, imagination develops as a child whereas it dwindles when entering teen ages. Linahon reports that when we do not foster this creativity during this age, we miss out on a lot of potential creativity that can show us when problem-solving outside of the artistic domain and in the classroom setting. Luckily Linahon notices a changing dialogue among educators.

“If you don’t have creativity, or the ability to use your imagination to think outside the box, you’re not going to improve or get anywhere. And it’s cool that our society is starting to change in this way. Things like the 21st Century Skills are what is going to help people succeed in the workforce because it is more about teamwork, collaboration, innovation, and being creative. So when we’re not funding the art programs or cutting that out of schools, then people aren’t going to have an opportunity to practice their imaginations,” Linahon said.

Teacher sponsor Haley Johannesen feels that there are broad assumptions about teenagers’ creative activity coming out of COVID-19 isolation. In reality students are creating more, just in new and different ways. To Johannesen, submitting to the Review is a way to prove that teenagers are creative.

“A lot of students can have a hard time with there not being a correct answer in writing, therefore, it’s a scary thing to do. Writing is vulnerable, the fact that there isn’t necessarily a correct answer gives you the other side of it, the glass half full, the leeway to be creative in what you write and what you express,” Johannesen said. “The Review is not just a place where you’re submitting your art, you are taking a stand for art. I encourage students to push limits, be vulnerable. Try something even if they’re not sure how it will land, just so that you can get the feedback that you need. Writing is for everybody. You just have to put the time in.”