Freedom of Speech, Interrupted

City High’s Statue of Liberty stands tall on the edge of campus

“We do not support so-called ‘trigger warnings,’ we do not cancel invited speakers because their topics might prove controversial, and we do not condone the creation of intellectual ‘safe spaces’ where individuals can retreat from ideas and perspectives at odds with their own.”

These were the words sent out in a letter to this year’s incoming freshman at the University of Chicago, opening up the debate about free speech on college campuses anew. This debate, over the need to protect free speech versus the need to protect disadvantaged students whose rights to a safe and comfortable educational environment can be violated by that freedom, is a long standing issue. The University of Chicago has stood out from the rest, refusing to compromise their educational values even in the face of student opposition. Intentionally or not, they have become the stalwart defender of the freedom of speech, regardless of its potential for harm or controversy.

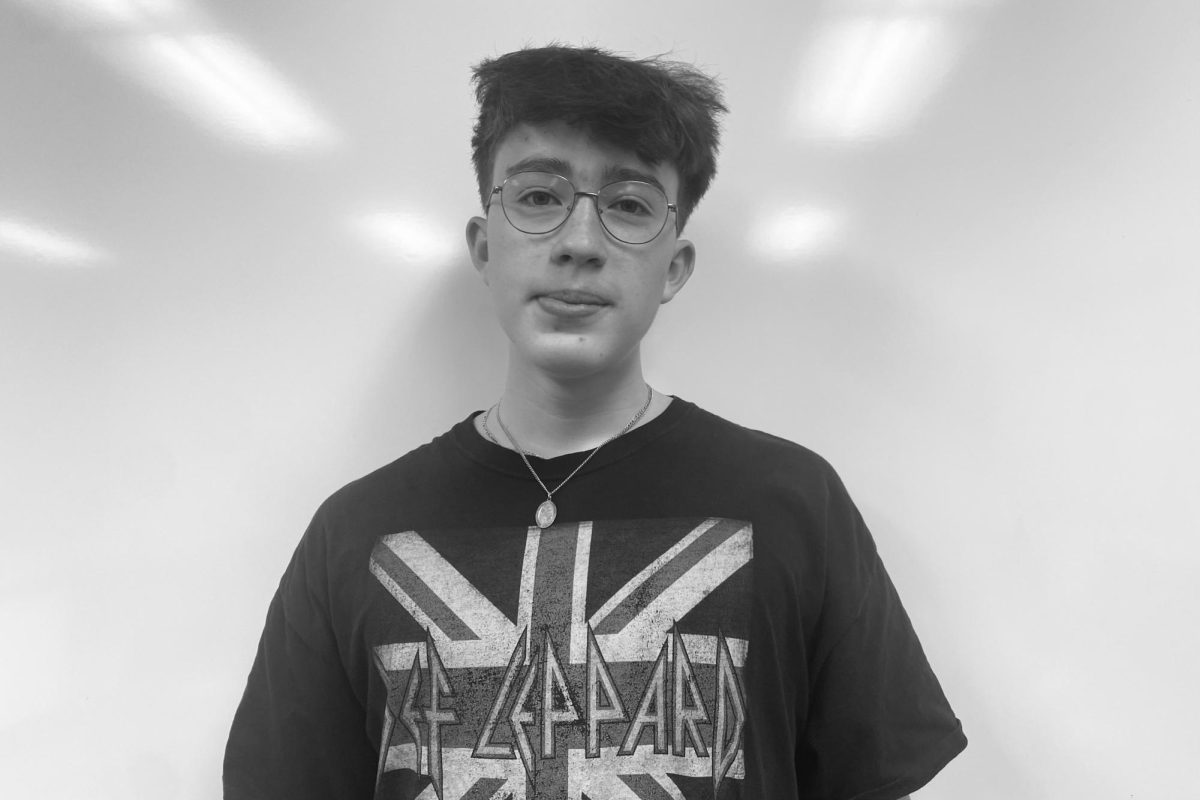

On this polarizing issue, high school students like Max Meyer ‘18 often have strong opinions.

It’s good to know that some people are still serious about freedom of speech. I don’t ever want to feel like I’m unwelcome express my opinion. — Max Meyer

“It’s good to know that some people are still serious about freedom of speech. I don’t ever want to feel like I’m unwelcome express my opinion,” said Meyer. “The 1st amendment protects freedom of speech. It doesn’t say that you’re free to say what you want as long as it doesn’t offend anyone.”

Despite its stance on free speech, Chicago has had issues recently with students shutting down speakers invited to the school. One such incident occurred this February, when Anita Alvarez, the Cook County State’s Attorney, had planned to give a speech at a forum at the University. She was unable to speak and was forced to leave by protesters who disrupted the event.

This incident at Chicago reflects a growing concern on college campuses nationwide. At almost every school, speakers from various backgrounds have had their speeches either cancelled by universities following student protest or were interrupted by said student protests. These incidents are not limited solely to speakers; Wesleyan’s student newspaper had their funding revoked by the student government following an article criticizing the Black Lives Matter movement and Ayaan Hirsi Ali, a feminist author and activist who was set to receive an honorary degree from Brandeis University, had her degree canceled following student protest over her views on Islam.

Issues like this strike at the heart of college towns like Iowa City. The University of Iowa has seen its fair share of incidents over this topic. In 2014, a statue by faculty member Serhat Tanyolacar, which was covered in old newspaper clippings on the KKK, was taken down following complaints of racism by Iowa students. Despite its intended anti-racism message, many students felt the statue was a threat to their safety. Even more recently, this August, UI professor Resmiye Oral launched a campaign against the facial expressions of the school mascot. In an email to fellow professors, the professor claimed that some of the images of Herky “are totally against the nonviolent, all accepting, nondiscriminatory messages we are trying to convey through campus.” In fact, in 2015, the University of Iowa made the list of the 10 worst schools for free speech compiled by the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education.

The University of Chicago and the University of Iowa have had very different responses to the controversies on their campuses. The U Chicago letter itself was prompted by a report released in 2015 by Chicago’s Committee on Freedom of Expression, which detailed the long history of free speech at the University and reaffirmed the school’s commitment to the value. It established that while the school believes in “civility and mutual respect,” it is not the job of the school to enforce those values, but rather the job of individual people, with exceptions being made for cases of harassment and other misconduct.

No official policy changes accompanied the letter or the report; they were rather meant as an affirmation of the school’s historic values. The University of Chicago has stated that it will continue to offer community centers and resources to the campus’ minority and LGBT communities and will allow teachers to continue to use trigger warnings in what they deem to be appropriate and non-academically restrictive ways. Instead, the letter and report were targeting specifically the perceived restriction of free thought and free speech.

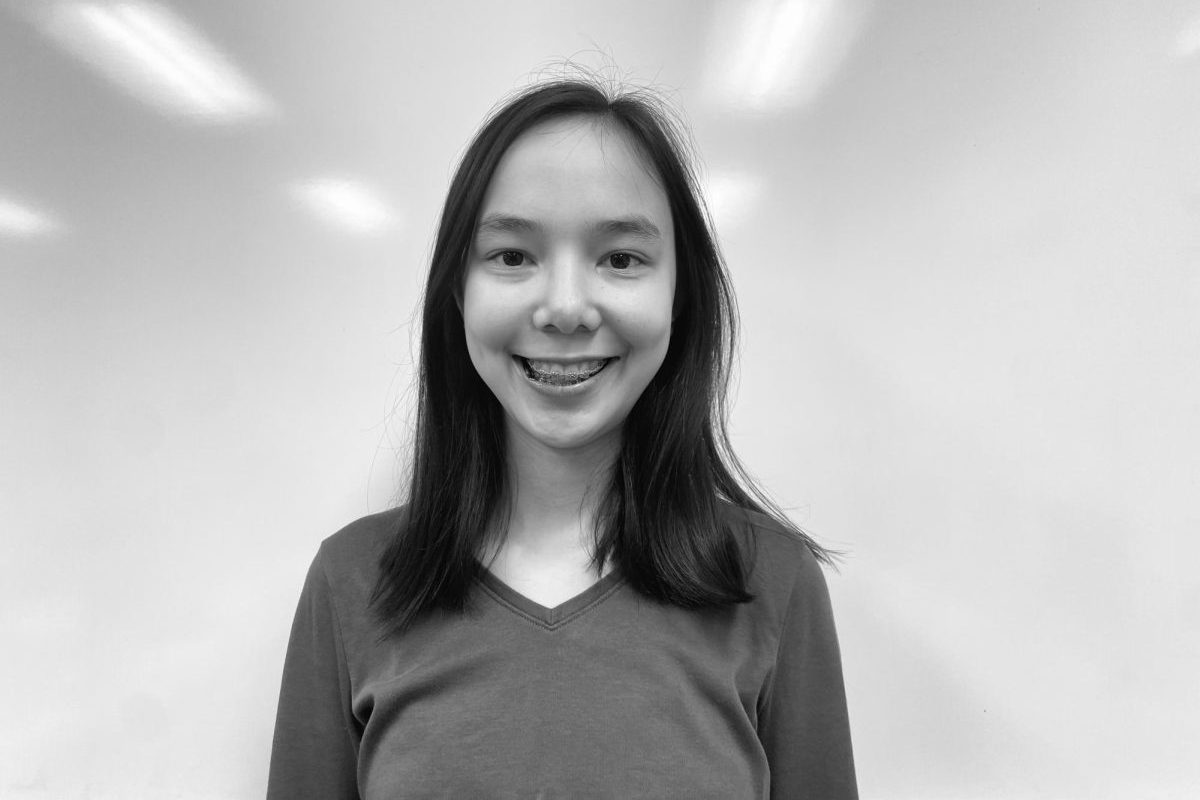

Anna Norman-Wikner ‘17 doesn’t believe that school did a good job conveying their point: “I support free speech in the classroom. But there need to be resources available. People need to have places that they can go.”

“This debate makes light of people who have actual triggers or PTSD,” said Michael Menietti ‘17. “As a result, people don’t believe them and it just makes it harder.”

This debate makes light of people who have actual triggers or PTSD — Michael Menietti

The UChicago report, more than just recalling platitudes spouted by administrators, also recounts other periods of conflict at the school over the issue. In 1932, William Z. Foster, the Communist candidate for president, was invited to speak at the school, angering people both in and outside of the school community. Responding to the controversy, President Robert M. Hutchins said that the “cure” for ideas we disagree with “lies through open discussion not inhibition.” Pressed later, he added that “universities exist for the sake of such inquiry, (and) that without it they cease to be universities.”

Norman-Wikner echoed that sentiment.

“I don’t support hate speech, but I think that you should be able to say and to believe what you want on a college campus, because that’s what college is about,” Norman-Wikner said. “People should have the ability to have a respectful disagreement within the classroom. They shouldn’t wall off one topic.”

If there are colleges that I’m looking at that told me they wouldn’t allow freedom of speech on campus, wouldn’t allow protests, wouldn’t allow open discussion in classrooms, then I’d automatically be thinking about other schools.

— Anna Norman-Wikner

As U Chicago holds resolves themselves to their free speech stance, the University of Iowa appears to have mainly stood firm in their stance, with only one minor change in policy. That change occurred in April, when a pro-life group on campus chalked 3,200 hearts on a frequently chalked walkway. Following student complaints, University officials washed away the group’s message, leaving art by other groups untouched. The University has since revised its policies on chalk art following complaints that similar displays were left up. Chalk art will be restricted to announcements of campus events, and will only be allowed to include the name of the event and the group holding it and its time and location.

Although the people most affected by campus free speech are current college students, this issue has a large impact on high school students as they decide the future of their education. The availability of both free speech and safe spaces can influence the schools students feel comfortable considering.

Menietti’s college search has certainly felt the impact of this issue.

“I hesitate to even look at bigger universities,” Menietti said, “You can’t have an opinion that’s not their opinion at bigger colleges.”

Like Menietti, Meyer also felt this issue affected the colleges he looked at.

“I can cross certain colleges off my list by default,” he said.

Norman-Wikner agreed as well: “If there are colleges that I’m looking at that told me they wouldn’t allow freedom of speech on campus, wouldn’t allow protests, wouldn’t allow open discussion in classrooms, then I’d automatically be thinking about other schools.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Iowa City High School. For 2023, we are trying to update our video and photo studio, purchase new cameras and attend journalism conferences.