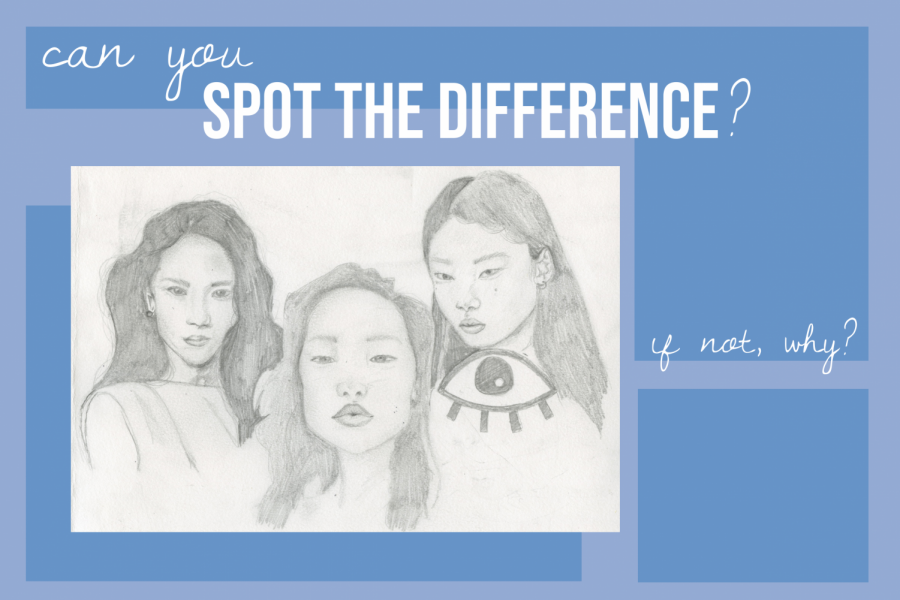

Not All Asians Look the Same

Art by Maha Mohammed

December 19, 2019

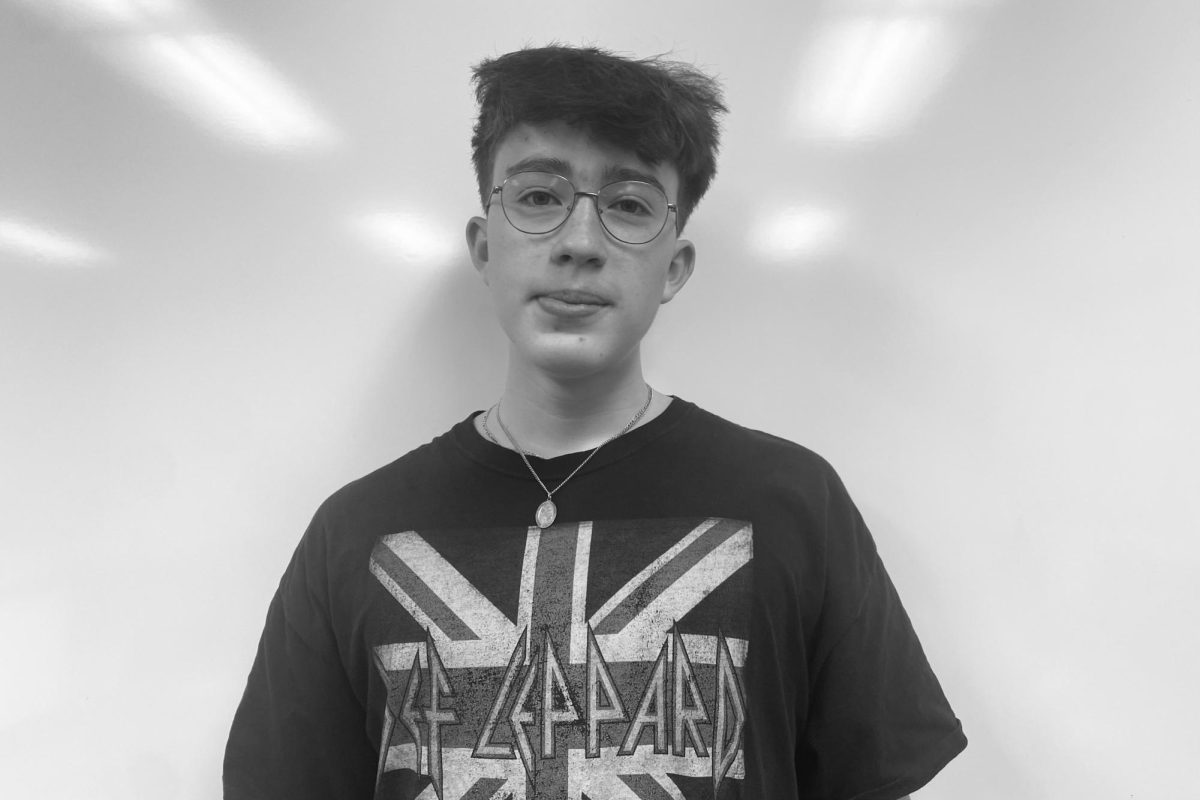

Facial recognition is a vital factor of human interaction. However, there’s one variable that can cause this function to falter. Most commonly referred to as “the cross-race effect” or “own-race bias,” cross-racial identification is when one tends to be less able to recognize individuals of a race other than one’s own. This may seem harmless, but it often leads to the misidentification of people of color.

In its most extreme state, own-race bias can lead to the misidentification of suspects in a police lineup, however, it can be a perpetual aspect of many people’s lives. This tendency has also commonly affected people of color and has been linked to the stereotype that “all Asians look alike.” This trend, however, doesn’t affect twins or doppelgangers, merely people who are less able to distinguish people of different races who, to people of their own race, look nothing alike. It isn’t a way to call people out for thinking one Asian person was really someone else.

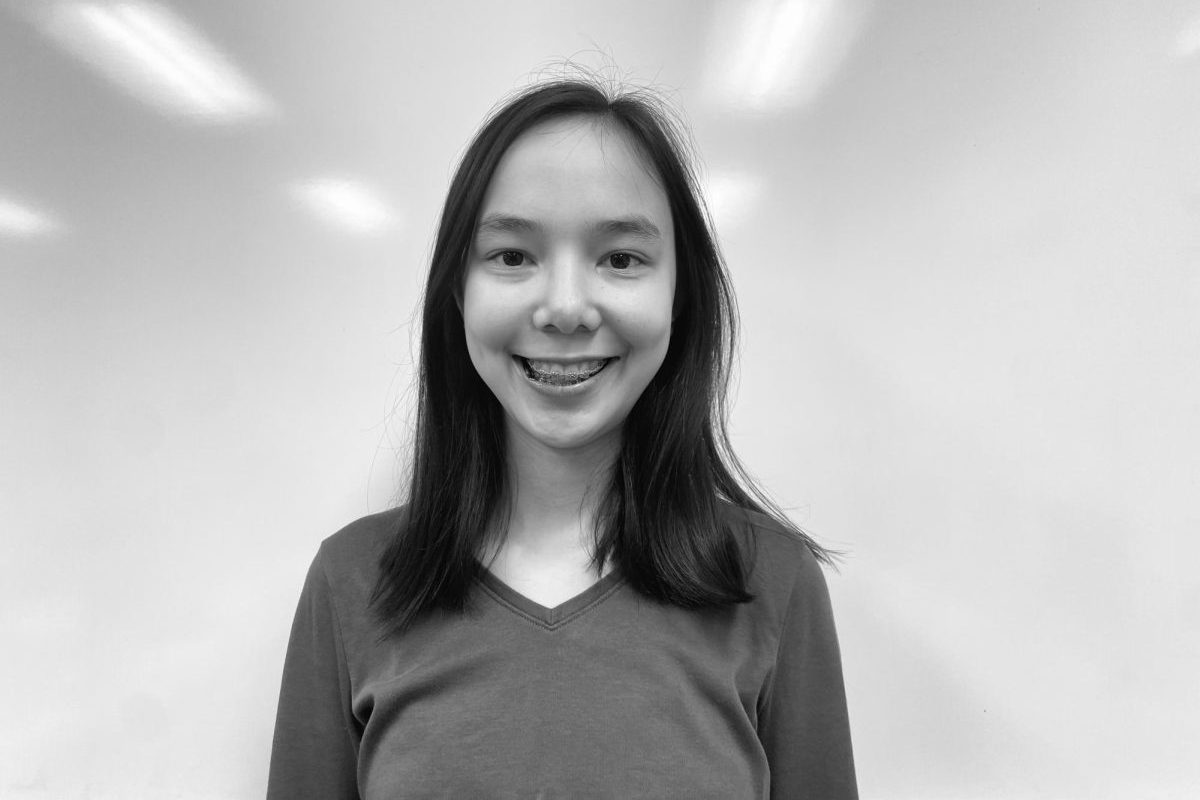

Forgetting the name of someone you’ve only met once or accidentally calling a friend the wrong name can happen to anyone, myself included. Those are honest mistakes, but they could often be a symptom of own-race bias. When people mistake me for another Asian student at school I know that they, hopefully, aren’t doing it maliciously. That being said, it can still be annoying.

People are called the wrong names by teachers and pestered with questions about their race and relations. Just because there is an effect that explains why these things may occur, doesn’t make it right. It’s frustrating being asked several times in one week if this one guy in band is your brother or accidentally being congratulated for being a lead in a play you definitely weren’t a part of. It removes the individuality of people who have to go through this daily.

Recently I was called by someone else’s name and congratulated for my performance in the play, which I had no part in. Confused at first, I said ‘thank you’ and went on with my day. Later I realized that they must have confused me for someone else in the play and I had just taken credit for their performance. I felt bad, but there wasn’t a way to fix it. In the moment I could’ve corrected them, but wouldn’t that be rude? Wouldn’t that just make the situation worse? What is the right thing to do in situations like that?

It sucks when you’re on the spot and someone praises you for an accomplishment that isn’t your own. You can either correct them and make the situation more awkward, take credit for something you didn’t do, or just freeze up and not know how to respond at all. There’s no rulebook on how to deal with situations like that.

Not only am I often confused with other, female, Asian students, but I’m also often asked if I am related to other Asian students at City High. People have asked me if I’m related to almost every other Asian (East Asian, South Asian, Southeast Asian, Central Asian, even Hawaiian and Middle Eastern) student at City High and they’re often surprised and confused when I tell them I’m not. I have been asked multiple times if I am related to the other Asian people band. Now most of the time I just say no and move on, because I don’t really have time to focus on those little microaggressions.

The worst part of all of this isn’t that I’m offended all the time or that it hurts my feelings because it doesn’t anymore. The worst part is how often it happens. How often it happens, and how I no longer seem to care. It’s so frustrating when you feel like people are ignoring who you really are and only seeing you for what you look like. Appearance isn’t the only way to know somebody and even though our society pushes this message on all of us, it should be something we can overcome. I’ve become complacent and I know this will only make it worse. There are a few things, though, that I think could help heal this “cross-race effect,” the first being the acknowledgment of personal biases and then simply make an effort to overcome them. It’s okay if you can’t tell the difference between Lucy Liu, Ming-Na Wen, and Michelle Yeoh. Just work on getting better. Like with all things, practice can greatly improve your ability to distinguish the faces of people who aren’t the same race as you. Validating the people around you by understanding their struggles, or expressing how you feel invalidated, will be beneficial to everyone and form even stronger connections.

Jackie • Apr 15, 2023 at 11:59 pm

Asians are also the same with Whites. They can’t tell the difference between a Dutch and a German or between a White American and British. Frankly I also having hard time distinguishing between Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos, Thais, Vietnamese. Its an honest mistake and not a means of insulting people.

Lisa • Mar 21, 2022 at 7:45 pm

I had a Vietnamese friend who once showed me a photo of herself in a group of schoolgirls in the 1960s. She HERSELF wasn’t even sure which one she was! All the girls looked very much alike with the same coloring, similar facial features, and even the same hairstyles (dutch boy cuts with bangs.) So if my friend had trouble identifying herself in the photo, why is it so hard to understand why it is sometimes difficult for me – as a white person – to differentiate between them? In a group of white American schoolchildren, they would have different hair colors and textures, different eye colors, and different complexions so the variety in their appearances would make it easier to tell one from another.