“Re-Education Camps” Detaining Uyghur Muslims in China

City High students discuss mass detention of Uyghur Muslims within the northwestern Chinese region of Xinjiang, and how it is raising fear among Muslims in America

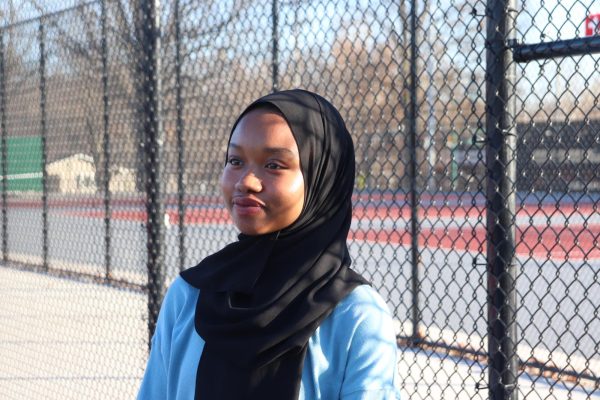

Riem Hassan ’20 is silenced, evoking the silencing of Uyghur Muslim populations in China.

February 27, 2020

Buses and cars lay strewn across the street, their windshields crushed into minuscule glass shards. A combination of broken engines billowed black smoke into the air, while armored police shot tear gas into crowds of protestors. Bystanders ran amok, trying to escape the increasingly vicious confrontations.

This scene of disarray and violence became known as the 2009 Ürümqi riots. Provoked by Uyghurs Muslims’ discontent with an unsubstantiated rape allegation in the province of Guandong, hundreds of workers participated in a brawl at a factory in which at least two Uyghurs were killed by Han Chinese, the majority ethnicity in China. The news spread rapidly to the Uyghur majority region of Xinjiang, where bellicose Uyghurs clashed with Chinese Armed Police, ultimately leading to a death toll of 197 people.

Displeased with the violence they saw in Xinjiang, Chinese government officials deliberated extensively on their response to what they saw as an extremist group. In 2014, Chinese governmental figures began a program known officially now as the Xinjiang Vocational Education and Training Centers, or Xinjiang re-education camps. An estimated 25 percent of all Uyghurs were rounded up in the span of a few years and placed into camps meant to indoctrinate them into the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) core beliefs. Uyghurs who were not chosen for re-education in camps were prohibited from speaking any foreign language and forced to have pork and alcohol in their homes, both of which are prohibited items in their Islamic religion.

Feda Elbadri ‘21, who identifies as Muslim, sees the re-education centers as a targeted attack on those with Islamic beliefs.

“Something so large-scale seems like a targeted method of erasure under the false guise of ‘ridding the country of terror,’” Elbadri said. “It seems like the government sees them as a problem they want to disappear.”

In a series of documents leaked to the New York Times in 2019, Chinese officials detailed a re-education campaign of “no mercy.” Nicknamed “The China Cables,” the documents detailed a scheme to detain over 1 million Uighur Muslims in various different camps, each with their own individual purpose. Detainees must study the thoughts and important work of Chinese president Xi Jinping, and spend hours memorizing Chinese propaganda songs and confess invented sins. Some camps are utilized for mass detention, where detainees have been known to disappear. Elbadri sees this as a targeted effort to create uniformity within China; consequently, this means the erasure of Islamic culture within the country.

“I don’t like hearing about people who are Muslim, or people of any faith for that matter, being targeted in such a way. It deeply troubles me when non-Muslims explain terroristic behavior as some sort of branch of my religion,” said Elbadri.

Life outside of the camps, in the Chinese province of Xinjiang, is no better. Uyghurs must install a spyware app called “Xi Jinping” so the government can monitor their daily activity. The app’s facial recognition can capture who is passing by a mosque and punish them for doing so. Chinese police forces monitor over 1 million Uyghur Muslim homes, creating a sense of omnipresent surveillance. They’re in a training school set up by the government — Leaked Chinese Document Detailing Reeducation Camps

Nury Turkel, the former executive of the Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP), believes the Chinese government’s response represents the quelling of a religion the CCP believes is out of line with its main ideology.

“What they’re trying to do is to stamp out Uyghur identity and also make them atheists, believing in communist ideology, simply because to the Chinese government or Chinese thought leaders, Uyghur Islam is a sign of disloyalty. As long as the Uyghurs maintain their cultural identity, ethnic identity, and religious practices, the Chinese government believes that it will potentially become a political threat,” Turkel said. “Even if you look at the people who are locked up, and their policy objectives, their ultimate goals are all based on preemption.”

The Chinese government has argued that its motives for the creation of the camps are ethical, as they are meant to reduce terrorism. However, there are many economic motives for creating Chinese control in Xinjiang. The region, situated in Northwest China, is saturated with natural resources essential to China’s recent rapid economic growth. As many Chinese citizens equate the country’s fiscal success with their assessment of the Chinese government, maintaining prosperity is paramount to president Xi Jinping. Jennifer Lin, a senior at the University of Iowa whose family is from the province of Fuzhou, believes that the majority of Chinese people are indifferent to the situation as economic growth has been maintained.

“I feel like a lot of [Chinese people] are apathetic with the situation because it doesn’t really involve them,” Lin said. They have not committed a crime, and will not be punished. They have just been confused by unhealthy thoughts. — Leaked Chinese Document Detailing Reeducation Camp Policy

Chinese people also lack the entirety of freedom of speech that citizens of the United States are used to in their daily lives. Consequently, speaking out against government transgressions is not as simple as making a negative post on social media.

“It’s hard for Chinese people to even be supportive of the Uyghurs without offending the government and then having the government come after [them],” Lin said. “If they even attempt to support them or even help them out, they could get in trouble.”

An article released in July of 2019 by CNN reported that ambassadors from over 37 countries consisting of Saudi Arabia, Syria, Qatar, the UAE, Bahrain, Sudan, Pakistan and more, have encouraged the events happening in Xinjiang and even praised China for their actions. In a formally composed letter from the countries’ ambassadors, China’s education camps were routinely dismissed, with one country claiming, “China’s re-education camps are remarkable achievements in the field of human rights”.

However, in early October 2019, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo spoke out criticizing China’s treatment of Uyghur Muslims during a Vatican conference. Many questions were raised about the nature of Pompeo’s statements, which definitively criticized China’s camps as “internment camps” housing over one million Uyghurs. Due to such alarming statistics about the scope of the re-education centers, Albadri believes the issue should receive appropriate attention and action.

“Something has to be done, of course, and it starts with carrying on the conversation. Not just mentioning it once or twice, but learning what you can and furthering a discussion in various environments,” Elbadri said. “We have the advantage of living in a digital age where information can be put out into the world easily. The Internet and social media have been excellent tools during the revolution, such as media sharing during the Arab Spring,”

Young influencers from the Muslim community have spoken out against these events, primarily on social media platforms like Tiktok. Many videos have gone viral by raising awareness of the overall issue. Elbadri believes using social media as a medium to increase public knowledge about the events is the best way to encourage action.

“I think the best course of action for a high schooler such as I, before doing anything, is being informed and sharing what you find—maybe on social media, maybe in real life, maybe both,” said Elbadri. “You can never underestimate the power of a ‘share’ button—it can save lives and inspire change.”