Farming Green

With climate change and environmental concerns on the rise, farmers are starting not only to recognize their contributions to environmental degradation, but also the effects climate change has on them

With climate change and environmental concerns on the rise, farmers are starting not only to recognize their contributions to environmental degradation, but also the effects climate change has on them

May 15, 2020

Iowa is a state known for farming, leading the nation in corn, soybean, pork, and egg production according to the U.S Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Statistics Service. In 2012, there were 30,622,731 acres of farmland in Iowa according to the Iowa Data Center. However, according to the National Environmental Protection Agency, agriculture is responsible for nine percent of national carbon emissions.

“First of all, farmers are regular human beings, good human beings that are stuck kind of in a bad place. There’s been legislation that has encouraged that bad behavior,” Liz Maas, an assistant environmental science professor at Kirkwood Community College, said. “We don’t incentivize the right types of behaviors, or we don’t incentivize the right types of behaviors enough.”

According to Maas, there are many environmental concerns related to farming. Water quality, soil degradation, and carbon emissions are just a few.

“The system is just kind of rigged against [farmers]. And so it’s hard for them to use [fewer] chemicals or for them to make different decisions about the acreage that they have and how it could maybe be protected with buffer strips,” Maas said.

Many farmers are forced to farm the way they do because of economic restraints. The Triple Bottom Line is a framework that says you need to analyze issues not only from an economic perspective but from an environmental and social lens as well. Many environmental issues in Iowa become more complex when you look at the issues from all three lenses.

“If you think of a Venn diagram of those three pieces, [environmental, social, economic], sort of overlapping, that sweet spot that we cite, we environmental scientists call it sustainability,” Maas said. “I don’t like the term sustainability because sustainability is just sort of like getting a ‘C.’ It’s kind of just doing barely enough to get by so that we can keep, keep going sustain right and we need to at least get a ‘C.’”

There are many economic factors, such as monopolies on seeds, like Monsanto, that make it difficult for Iowa farmers to become more sustainable. Although there are some government incentives such as the Wetlands Reserve Program and the Conservation Reserve Program, they are optional.

“If [there isn’t a balance between social, economic, and environmental], then somebody’s going to get hurt so that kind of brings you to that next piece of your social justice issues, [the] triple bottom line is huge for social justice issues as well,” Maas said.

According to a University of Iowa researcher, Chris Jones, Iowa leads the nation in fecal production. This is attributed to Iowa’s large population of livestock. Although Iowa is a state of only 3.2 million people, due to the 110 million chicken, pigs, cattle, and turkey, we produce waste equivalent to 168 million people. This waste has an impact on Iowa’s water quality, which has high levels of nitrates and often requires “do not drink” orders. The quality is worsened by pesticides and fertilizers used for the state’s crops. According to National Geographic, Iowa is the second-largest nitrate contributor to the gulf in the Mississippi River Basin.

“I make my own personal food choices and I advocate for personal choices because of my concern for water quality,” Maas, who tries to lessen her meat consumption, said.

Sailesh Rao is the founder and executive director of Climate Healers, a non-profit dedicated to healing the earth’s climate. His research shows that shutting down the animal agricultural industry should be a priority when it comes to environmental issues.

“I’m especially thrilled with non-profit entities like Sadhana Forest who are creating perennial, edible food forests comprising fruit and nut trees, vegetable and berry shrubs, herbs and root vegetables that can be foraged year around,” Rao said. “Sadhana Forest is a completely vegan organization [that] uses composting toilets and other well thought out waste recycling processes to implement sustainability.”

Rao believes a vegan or vegetarian lifestyle is ideal for the climate and the planet.

“Animal agriculture uses 37 percent of the land area of the planet just to graze animals and this grazing land currently stores just two percent of the land carbon. If the carbon storage on this grazing land were increased from two percent to 20 percent, we can literally reverse climate change,” Rao said.

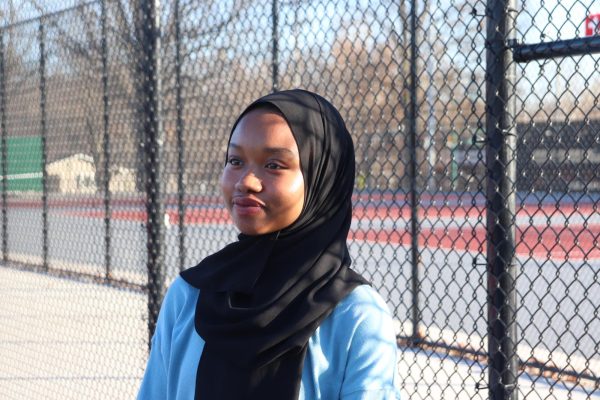

However, farmers aren’t only contributing to climate change and environmental degradation. Farmers across Iowa are also feeling the effects of climate change. Katie Hagan’s family owns a farm in Wellman, Iowa. Hagan has been seeing an increase of flooding which has affected her family’s planting, especially last year’s flooding in the spring and summer of 2019.

“[Last season] we weren’t able to plant our corn when we were supposed to. We had to plant it really late which means we weren’t able to harvest it until it was snowing already. And usually, we’re able to harvest it way before that,” Hagan said.

The floods of both 2011 and 2019 in Iowa were considered “500-year floods”.

“A 500-year flood event just means that you’re supposed to have one every 500 years. Statistically speaking, now we shouldn’t have any more for another at least 1000 years.

But I don’t think that that’s probably going to be the case,” Maas said.

Hagan has also seen other effects of harsher and more unpredictable weather patterns caused by climate change.

“I would say it’s been getting really cold, a lot earlier. We don’t really have a fall which is our main harvest season which means it’s harder for us to harvest especially when it’s snowing outside,” Hagan said.

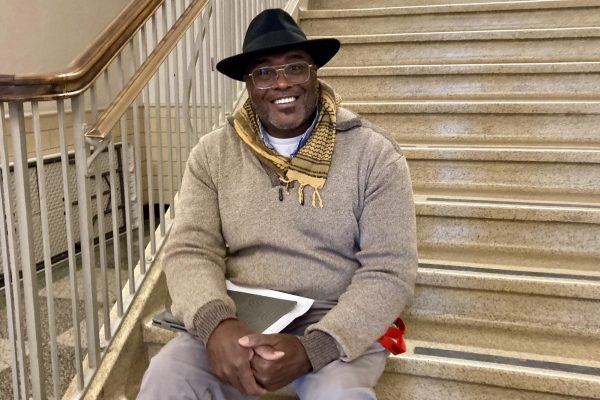

Nathan Bradford’s ‘22 family owns a hobby farm, meaning his family doesn’t farm for a living. His family has also felt the effects of climate change.

“There have been really brutal winters that can be especially hard on the animals. We have lost animals before due to the severe cold, as well as we’ve had some that have done the exact opposite where even though we keep the water maintained, they just can’t get enough, and they end up dying from thirst [during drought],” Bradford said.

Not only are farmers feeling the effects of climate change, but some farmers are also trying to fight it. Some farmers try to utilize different energy sources, such as wind and solar.

Small and local farms try to reduce carbon emissions by running operations on a smaller scale as well as having less of a need for widespread transport. Organic farms are trying to be more environmentally mindful when farming by reducing the pesticides and chemicals in the waterways.

“The effect [of chemicals and GMOs] on the ecosystems is definitely evident, there’s enough research there to prove that this is affecting it, but the real hard part is the farmers are in a hard place as even if they don’t want to be using these GMOs and these pesticides, the economic part of it is if they don’t use them, their yields may go down because their ground isn’t naturally [ready] to handle that,” Bradford said. “They could be faced with a couple of really hard economic years if they tried to go into a non-GMO, non-pesticide state.”

Maas believes it will take a systematic change for farmers to have less of a contribution to climate change.

“With new leadership, we may have some new opportunities and look into the mission [to replace] older ideas about how things are supposed to operate and coming in with new ideas of how we could do this. It is always challenging, change is always hard,” Maas said. “There’s a lot of people that are in leadership that still don’t accept climate science and still there are things that are changing, and even while we continue to have more extreme weather events.”

Bradford also believes there needs to be a systemic change in order to revolutionize how Iowans farm.

“There would just have to be a pretty universal push toward [organic],” Bradford said. “Like I said, it’s not fair for the one small farmer to stop using [pesticides] to get his yield so far down that he can’t compete anywhere near with the other frontrunners, even though they are dumping these things into our ecosystem.”

Hagan agrees that it takes governmental action to help protect the environment.

“We could definitely start [acting against climate change] by having a president who thinks climate change is a real thing,” Hagan said.

Bradford wants people to know that climate change isn’t just affecting farmers.

“Even if you live in the city, climate change itself does affect people directly,” Bradford said. “While we can’t stop what we’ve already done we can, we can stop it from harming anymore.”