New ICCSD Grading System Pushes for Equity

New Policies Aimed at Emphasizing Learning Over Completion

Jill Humston, a science teacher at City High, is adapting to the new grading policies by focusing on learning standards.

Seven months after the implementation of a new grading system at City High, its effects, according to some teachers, are making grades more equitable. However, aspects of the new policy are still under discussion, and many issues are still in the process of being worked out.

The new grading system, an overhaul of grading standards across the board, was adapted by all high schools in the Iowa City Community School District, as part of an effort to create a more just and equitable system that focuses on mastery of material rather than participation scores, homework, and extra credit.

When asked whether the District had taken teacher feedback into consideration, Anna Basile, an English teacher, said that it was teacher-driven initiative.

“Grading is something that we as a faculty have been talking about for a long time,” Basile said.

A more equitable grading approach focuses on the idea that we want students to learn the material. People learn in different ways and we want to support and reward perseverance, with the ultimate goal that the learning will occur. So all of the different components that we have been working to implement are moving in that direction of more equitable grading practices, geared towards promoting student growth.

— Principal Bacon

The new system is focused on student mastery of key learning standards for each class.

“We recognize that not every student is going to master those standards at the exact same moment in time, in the exact same way,” Bacon said.

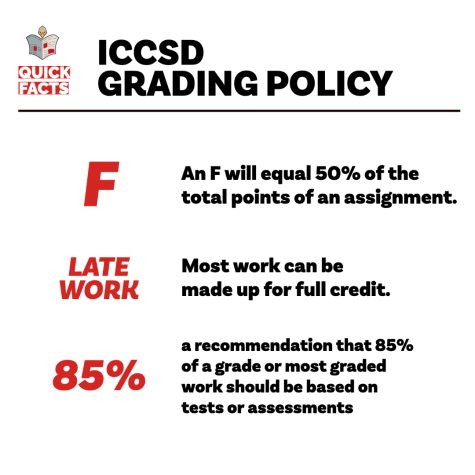

The new system downplays credit for class participation and completion of homework. A “50% clause” makes it impossible for students to earn less than 50% on an assignment.

The 50% clause was confusing for some teachers, like Danelle Knoche, when she started trying to implement the new policy in her classroom.

“The math behind it is called standards-based grading,” said Danelle Knoche, math instructor. “Where you’re graded on a scale. That’s similar to 4, 3, 2, 1, 0, where every grade is the same distance apart. But in the traditional grading scale, 60% of your grade could possibly be failing, whereas 10% is only allotted for each letter grade. So standards-based grading closes the gap and makes failing only 10%. Also, it makes it more equitable in showing what the student knows.”

Bacon, as well as several teachers at City High, made reference to an influential book by Joe Feldman called Grading for Equity. Joe Feldman is a long-time education and founder of Crescendo Education Group, consultants who work with schools around the U.S. to improve assessment methods.

Most of the ideas have been circulating for years, but the COVID-19 pandemic played a role in accelerating the change.

“One of the things during Covid that we were asked to do is really focus on essential things students need to know,” Dr. Jill Humston said. Students had much less in-class time, due to both online school and the hybrid model, and prioritization of the important standards became key.

“This [system] was around before Covid, but students definitely had a tougher time learning during Covid, so I think there has been a bigger shift towards these policies across the state,” Knoche said.

City High teachers expressed a variety of opinions about the new system. Some said that teacher interest brought about the change.

“The District got together a team of teachers, probably 30-40, from schools from across the secondary buildings and we met multiple times as a large group via Zoom,” Philip Lala, a science teacher, said.

Although other teachers were not consulted, they appreciate the effort to make grading at City High more equitable.

“It was primarily an administrative decision,” Ali Borger-Germann, English Language Arts teacher said. “I do not feel that I was ever asked for any level of feedback on that. I’m not sure I needed to be, I think it’s a good decision. I think the people who made it maybe didn’t implement it in the best way, but the result is that we’re doing things that are more just, and that’s always a good thing.”

Principal Bacon has said he believes teachers have autonomy in terms of what the policy will look like in their class.

“We probably have more work to do to identify what some of these practices look like in reality,” Bacon said.

Science teacher Thad Sheldon believes the new policy has shifted his grading to better reflect what students are understanding and away from measuring their mistakes.

“In the end, we want to give students multiple opportunities in varying formats to demonstrate their understanding. These shifts have focused our work, conversations, and time more on student learning and less on completing tasks or assignments.”

Some students are disappointed that the new policy eliminates extra credit.

“I think it should be included to give students more motivation,” Kenji Radley ’25 said. “I think it’s important. I’m disappointed that they don’t have extra credit.”

However, City High teachers understand the elimination of extra credit as an attempt to increase equity and promote actual mastery of the material.

“Providing extra credit to students with the sole purpose of adding points to a grade doesn’t exactly help us give an accurate reflection of what students understand. If anything, it inflates the grade,” Philip Lala said.

According to Borger-Germann, extra credit was also eliminated for equity reasons.

“Extra credit benefits kids who already have all of the benefits and all of the privilege, so it increases the privilege gap, and taking it away eliminates that as a factor,” Borger-Germann said. “Extra credit often rewards people who can have financial freedom to buy supplies, parental support at home, rides to school… All of that is just rewarding privilege. It’s not actually anything academic.”

Teachers do have some concerns. A primary concern mentioned by some teachers is that Infinite Campus still puts grades on a 100-point scale.

“The invisible math that the machine does behind the code, is still math, so it doesn’t matter what system you use,” Borger-Germann said. “It’s still creating a number value to grades that are on a 100-point scale, and that is somewhat inescapable by the nature of computer systems.”

When asked if Infinite Campus was going to be changed, Ms. Basile said, “That’s the million-dollar question.”

“It continues to be a major focus,” Bacon said. “The school district working with Infinite Campus to make everything line up properly.”

Other teachers expressed difficulty in lining up the new grading system with the learning process in their particular subject matter. For example, the new system emphasizes testing over practice with an “85% summative, 15% formative split.”

“The part of the grading policy that I’m a little unsure about is the 85% summative, 15% formative split,” Borger-Germann said. “And for me that’s primarily because in English, we often cycle through the same skill several times, and what that means is: either all of our assessments are summative, or all of them are formative. There’s no true divide between those things, the way there might be in, say, math or science, where you have a thing you have to learn in the unit, and then you either show mastery or you don’t, and then you move onto the next one. But in English, you might write analytically four or five different times. Which one is summative and which one is formative? As a teacher I’m learning, it’s part of my professional growth.”

“As with many initiatives or changes, there isn’t uniform commitment,” Sheldon said. “Many teachers feel the guidelines don’t go far enough, while others are resistant to the changes.”

Other teachers observed that the new system has not revealed a noticeable change in results.

“I don’t know if I’ve noticed a difference,” Humston said. “I think students who are doing homework that may have gotten good grades for completion of assignments are still getting good grades on exams because they were prepared. And now if you don’t do homework, your grade maybe was a zero, because you were missing the assignments. And now your test grade is gonna reflect that you didn’t do some of that practice to prepare.”

“I actually think we need a much more radical conversation about grading than the one that we’re having,” Borger-Germann said.

For many students, the effect of the change appears minimal.

“I’ve just been turning things in when they’re due,” Amy Anil ’23 said. “So I haven’t seen a big change in the grading. . . And even before the new grading system, many teachers didn’t offer extra credit anyways.”

“It hasn’t changed the way my grades look,” Noe Richman ’25 said. “But if I were to get an F on an assignment, at least it wouldn’t take my grade down like 15%. It’d still be doable for me to get my grade back up to that A.”

“It’s not like the whole grading system is being thrown out,” Bacon said. “We still issue letter grades and students still get an A, B, C, D, at the end of the trimester.”

For now, nothing is permanent. “The District continues to carefully study best practices in grading, and they want to allow teachers a bit of time and autonomy to strive to implement those best practices in a way that’s gonna work best in their classrooms,” Bacon said.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Iowa City High School. For 2023, we are trying to update our video and photo studio, purchase new cameras and attend journalism conferences.

Tai has been to public schools in three different countries. She enjoys eating spicy foods.