Problems With the Pipes

Proposed changes to the 2020 census have sparked outrage after the Department of Justice proposes a possible citizenship question which could be interpreted as targeting undocumented immigrants

May 8, 2018

The next decennial census is going to take place in 2020, and it is on track to include a question regarding citizenship that was not included in the last census. This question would be included because of a request from the Justice Department, according to a memo by Wilbur Ross, secretary of the Commerce Department, the overseeing department of the the Census Bureau. Within the form, it would ask recipients to mark if they and their family members were born in the U.S., born in a U.S. territory, born abroad with at least one U.S. citizen parent, are a naturalized citizen and the year of their naturalization, or the fifth and last category: “not a U.S. citizen.”

Those who are in favor of this addition claim that getting this information from everyone in the U.S. will improve the enforcement of the Voting Rights Act (which was written in 1965 and works to prevent the discrimination of minority voters) because counts of the voting-age population are used to ensure these protections. However, this announcement did not go unnoticed, nor did it go unopposed.

Those who are in favor of this addition claim that getting this information from everyone in the U.S. will improve the enforcement of the Voting Rights Act (which was written in 1965 and works to prevent the discrimination of minority voters) because counts of the voting-age population are used to ensure these protections. However, this announcement did not go unnoticed, nor did it go unopposed.

More than 25 cities and states are filing lawsuits against the question being added to the census (Philadelphia, San Francisco, Virginia, and Iowa are just some among them). The primary reason given as to why the question should be taken off the census dates back to 1787, within the writing of the Constitution.

Article I, Section II of the Constitution calls for an “actual enumeration” of the entire population, not just citizens.

“I think the biggest impact would be that we’re not going to get an accurate count of people living in America because people who are here who are immigrants, even legally, might not answer the question, or fill out the census, from the fear of deportation,” AP Government teacher John Burkle said.

The argument from this side is that the addition of the citizenship question will cause people or families who are not all fully citizens to not partake in the census, thus decreasing response rate, not counting the total population, and making it unconstitutional.

Aside from potentially breaking constitutional law, there are other impacts that this question would have if it was added to the decennial census. Jim Leach, a former congressman of 30 years and currently the Chair in Public Affairs and visiting Professor of Law and Senior Scholar at the University of Iowa, noted that the census controls some of the most important aspects in citizen interaction with the federal government: representation and funding.

“This [decennial census] data is used to allocate Congressional representation between the states. Hence Iowa, which at the turn of the 19th to the 20th centuries had 11 or 12 Congressmen, now has only four due to faster growth in other parts of the country,” Leach said. “The same data is also used internally to draw district lines for State House and Senate seats. In turn, this data is relevant to presidential determinations which are based on electoral college voting. Each state has the same number of electoral votes as it has a combination of the number of members of the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate.”

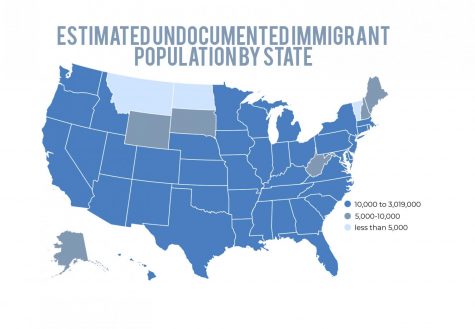

This structure would mean that if the states with high numbers of undocumented immigrants, such as California, New York, Florida, or Texas, had lower response rates, their representation in the House of Representatives could be smaller than it should be, and consequently, so would their influence in the deciding of the president and pieces of congressional legislation.

“This would take away the voice of everybody in those states, as well as those unauthorized immigrants,” Maryam Abuissa ‘20 said.

There are many implications for funding as well as representation.

“Many funding arrangements established in national legislation rely on distribution formulas tied to the decennial census, sometimes updated by states or communities between the census-taking, but not always,” Leach said.

The possible lower response rates of those states with high undocumented immigrant populations combined with these funding arrangements would result in those states, cities, and communities getting insufficient funding for health care, public education, housing, child care, job training, and transportation. The possible lack of access to these services has left some to wonder whether undocumented immigrants have the same rights as full citizens.

“Our Constitution is supposed to protect people equally, native-born or immigrated noncitizen, so I think that it is a pointless question at this point in time,” Burkle said. “We’ve always been a melting pot of a nation, so I don’t think we should ever target a group.”

It was also pointed out that in addition to discouraging undocumented immigrants from completing the census, this question has the potential to make them feel more marginalized.

“It just seems like a way to target unauthorized immigrants: make them feel scared or singled out,” Abuissa said.

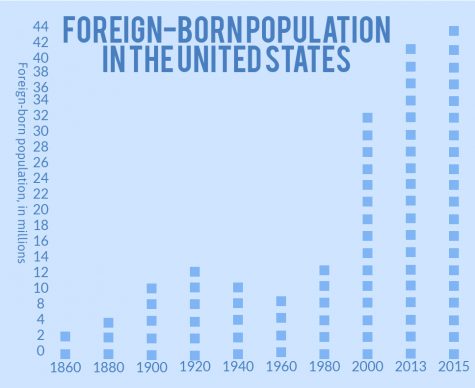

In 1787, it was decided that the brand new United States of America would enumerate the number of people within the nation every ten years, starting in 1790. Although the U.S. has completed 23 decennial censuses, it has not been without its controversies as is seen today.

“Every time in my memory the decennial census takes place, controversial elements related to the manner have developed,” Leach said. “States, communities and political parties have natural vested interests in the count due to the effects of census results on political reapportionment and governmental allocations of funds. It would not be abnormal to have a host of legal challenges.”

Not only have there been controversies surrounding the census before, but even more specifically, many changes have taken place in the way citizenship is dealt within the census, especially during the last 70 years.

“Well it’s been included before,” Burkle said. “It was included in the ‘50s. It’s not an awful question, it’s just linked to the current administration’s history of mistreating immigrants and non-American citizens of the U.S.”

1950 is the most recent year in which a decennial census that went out to every household in America included a question about citizenship. Ten years later, there was no question regarding status, only location of one’s birth. In 1970, the citizenship question was added back to the decennial census. However, a new system which contained one “short-form” questionnaire, which went out to five out of every six households in America, and one “long-form” questionnaire, which went out to the remaining one-sixth, was put into place. The citizenship question was only on the “long-form,” so most people in America did not have to answer it, along with the many other questions about those who lived with them only included on the “longform.”

After the 2000 census, the Census Bureau got rid of the longform census and replaced it with a smaller American Community Survey, which is sent out every year. The ACS only goes out to about 2.6 percent of American households—less than the long-form census; however, because of its frequency, it is used to gather data on trends in the U.S. between the censuses.

The ACS has been pointed to as a reason that the question regarding citizenship does not need to be included on the decennial census, because although it is small, it can be used to approximate the number of citizens versus non-citizens in the U.S.

Many believe that the policies and proposals concerning immigrants right now should be aiming to create less tension and more security.

“I don’t think it’s a needed question right now. I think that the government needs to figure out how to protect Dreamers and immigrants,” Burkle said.

The reason someone who is a family member of someone who is undocumented, or undocumented themselves, might not complete or send in their census often comes down to the fear of deportation.

Although the federal law is clear in stating that the Census Bureau is not permitted to share information about individuals with other federal agencies, so the fear of deportation should not be a factor when filling out the census, the law has been circumvented before:iIn 1940, the Census Bureau helped the government round up Americans of Japanese ancestry into internment camps.

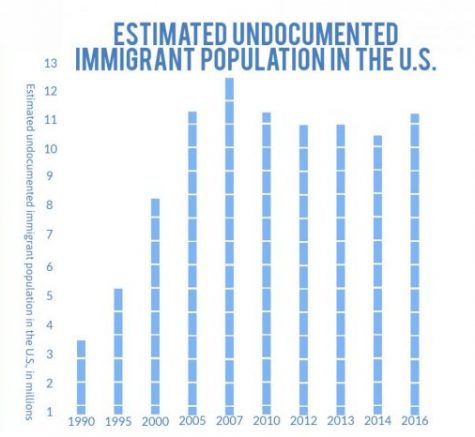

According to the Chicago Tribune and The Guardian, the past two years have seen dramatic decreases in the number of crime reports and usage of health services in communities in the U.S. with high undocumented immigrant populations. These trends have been attributed to the increasing desire of not wanting to draw attention to one’s self or community, in the case of possible deportation due the current climate of nationalism, increased xenophobia, and the administration’s proclaimed “crackdown on illegal immigrants.”

The fear of deportation and the careful ways of life necessary to remain safe and with one’s family is not new or surprising, even within City High.

“Of all of the adults in my family, only one is a U.S. citizen. I have about 10 aunts and uncles who aren’t full citizens: three are undocumented and at risk for deportation. My parents have their legal residency, but my dad isn’t allowed to leave the country or else he’ll get deported,” Mary* said. “My uncle was deported because he was caught drinking and driving twice to work–he was a legal resident back then. But everyone else in my family is extremely careful.”

In the unlikely event that the Census Bureau shares information that leads to the deportation of undocumented immigrants, it is not just those people’s lives that will be impacted. Deportation has strong emotional effects on friends and family members, too.

“It broke my heart to see my favorite uncle leave. We always hung out and he was a great person. I still talk to him over FaceTime and hope that someday I’ll be able to fly to Guatemala and visit the rest of my family over there,” Mary said.

The question of citizenship status on the 2020 census is not planned to be removed thus far. However, because of the many U.S. civil liberty groups, immigrant communities, cities, and states suing to block the question, the present state of the census could change before it is sent out to individuals and families around the nation in two years. Whether it changes or not, the controversy has reminded many people in the U.S. to appreciate the work of those around them, despite any lack of documentation they may have, and to defend each other’s safety.

“The census should be used as a tool to help the nation and all of the people who live and contribute within its boundaries,” Owen Sorenson ‘20 said.

*Name has been changed to protect anonymity of student