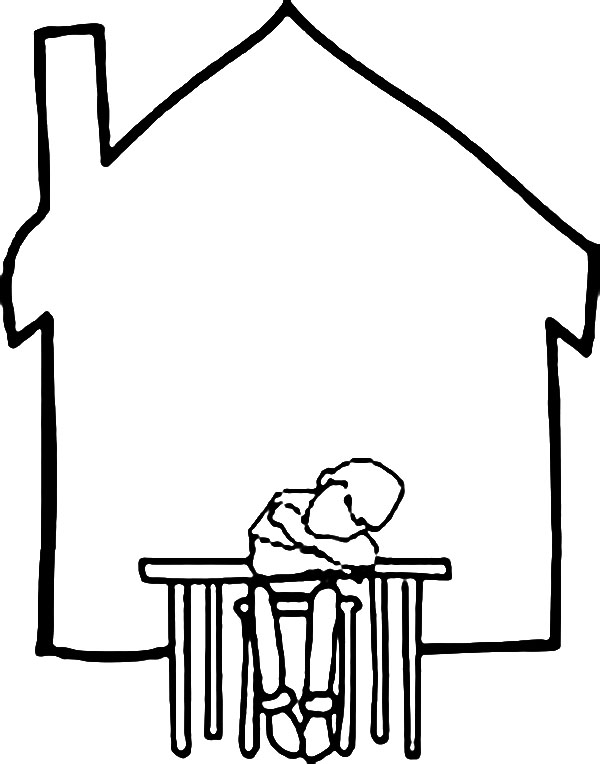

Teen Homelessness: A Silent Struggle

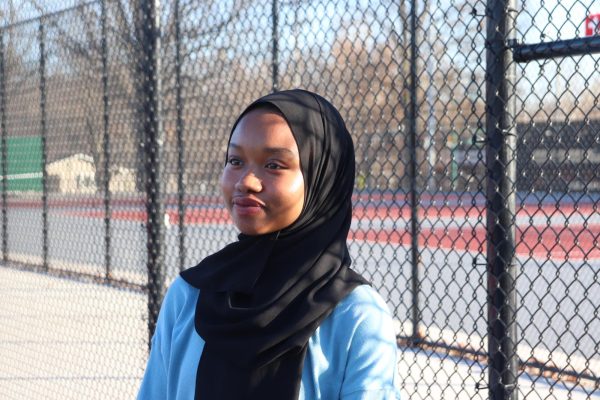

Homeless students are confronted with unique challenges.

A Silent Struggle

When many people picture homelessness, they conjure up images of middle-aged men with unruly beards living in shelters or out on the streets. However, being homeless does not always mean you are living on the streets.

According to Amy Kahle, a Student Family Advocate [SFA] at City High, there are 1,236,323 unaccompanied youth nationally. One federal report shows 6,789 homeless students enrolled in Iowa schools for the 2016-17 school year. In the Iowa City School District alone, there are 456 recorded unaccompanied youth.

“Each new student that gets to City High fills out a new student questionnaire in the office that asks a question about their homeless status or lack thereof, and so if that’s flagged then they get referred to Thos [Trefz, an SFA] or I,” said Kahle. “Whether they ran away or whether [students] were kicked out doesn’t matter; as long as they aren’t under the roof of a legal parent or guardian, then they’re unaccompanied.” Whether they ran away or whether [students] were kicked out doesn’t matter; as long as they aren’t under the roof of a legal parent or guardian, then they’re unaccompanied. — Amy Kahle

By the definition given in the McKinney-Vento Act of 1987, the word “homeless” denotes individuals who lack “a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence,” or additionally, a child or youth who is not in the physical custody of a parent or guardian. This definition includes those who lack a permanent home and may be “doubled up,” or staying with friends and relatives, as a result of housing or economic hardship or other extenuating circumstances.

Students whose living situations change during the school year are more difficult to flag. In those instances, there is no way for school administrators to know that these newly homeless students need additional support unless they choose to identify themselves. If not, Kahle said, they must face a slew of challenges and barriers alone.

“You might not get enough sleep, you might be really tired.You might be anxious,” said Kahle. “All of those little tiny hidden fees in high school like a cap and gown for graduation, t-shirts or athletic things that you might need–or that most high school students might take for granted [because] their parents might just give them ten bucks or 30 or 50 dollars to get something–that’s not always available for homeless youth or unaccompanied youth.”

Indicators that a teen does not have fixed housing may include falling asleep in class, poor attendance, anger and behavioral issues, and hoarding food. Identifying McKinney-Vento-eligible students can be a difficult process because of the level of trust needed in order for them to reveal their situation and face the stigma of being homeless.

McKinney-Vento provides several protections. Qualifying students have the right to be enrolled at educational institutions without a transcript, free lunch without needing to apply, and help with transportation to and from school if needed, among other things. Students under McKinney-Vento have full access to their rights regardless of whether they have run away from home, been kicked out by parents or guardians, or live, along with their families, without fixed housing.

Garcon Personne* is a teen attending school in the Iowa City Community School District. The summer before the 2018-2019 school year started, he ended up being kicked out of the house following a disagreement with his family.

“I had to find a place to live and the school was like ‘Hey, try UAY!’” Personne said.

Despite being advised to do so, Personne did not initially go into the Transitional Living Program at the UAY.

“I just needed to do one thing at a time,” said Personne. “I was still trying to process, like, ‘Why did my dad kick me out? What’s happening in my life right now?’ So it’s like, focus on one thing first.”

“I just needed to do one thing at a time. I was still trying to process, like, ‘Why did my dad kick me out? What’s happening in my life right now?’ So it’s like, focus on one thing first,” Personne said. I just needed to do one thing at a time. I was still trying to process, like, ‘Why did my dad kick me out? What’s happening in my life right now?’ So it’s like, focus on one thing first. — Garcon Personne*

Instead, Personne chose to couch surf for several months, living with friends, family, and even teachers at school. At times, Personne even found himself sleeping outside.

“School is number one first,” said Personne. “[Last summer], I came to school, talked to the school, had to get Thos involved so he could find a way to get me help and everything and so I’m good right now for school. Plus, me being in the homeless status gets me a full-ride to Kirkwood for free.”

According to Smith, who is one of three people (two full-time) staffing the Transitional Living Program has been around for somewhere around 40 years now. Despite its longevity, many homeless and unaccompanied teens are still unaware of the resources available to them through TLP and other local lodging services.

“We [at the UAY], we’re pretty sure that there’s some individuals who don’t even know who we are [who are] dealing with these types of situations,” said Smith. “We want to figure out how we can get to those individuals because they need us. That’s what we’re here for.”

THE TRANSITIONAL LIVING PROGRAM

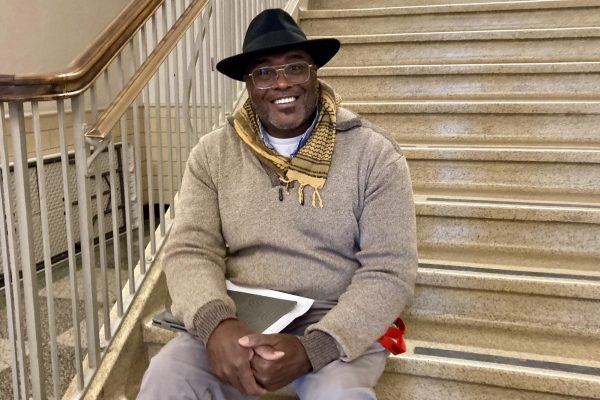

For Emerald Smith, Tuesdays through Saturdays typically consist of the same sequence of events. She checks her daily appointments to see who she will meet with on that day. Each meeting will last for about an hour. Later, at her desk, she will document how each meeting went.

For the last eight years, Smith has been working as a homeless youth advocate with the United Action for Youth Transitional Living Program [TLP].

“I have a history of working with youth, working with juveniles, youth who are at-risk, who are basically seen as a “problem child,’” said Smith.

In Iowa City, there are several resources for homeless individuals, among which include the Domestic Violence Intervention Program, Shelter House, Catholic Worker House, and the UAY Transitional Living Program.

The Transitional Living Program is unique in that it provides services to those ages 16-21. This means even those who are not yet 18, and therefore, cannot access the other safe housing options, such as the Shelter House, can be provided with living services.

“If it’s housing that they’re looking for, we do have a couple of homes, where if they meet criteria and eligibility, they can move in for up to 18 months,” said Smith. “During that time, we’ll be able to teach them the basic skills of survival. By the time [TLP members] move out within that 18 months, our goal is to already have somewhere they can move to, somewhere stable, so they can make sure that homelessness does not come back into the picture again,” Smith said.

The Transitional Living Program, though its name may indicate otherwise, does not merely provide housing services. Keeping in line with the goals of the United Action for Youth, the TLP’s mission is to uplift.

“Our focus is to empower, whether…it’s being through counseling [or] appearing for someone who may not have the confidence to speak up,” Smith said. Our focus is to empower, whether…it’s being through counseling [or] appearing for someone who may not have the confidence to speak up. — Emerald Smith

Though it may provide many services, the TLP is not without its flaws. Since there are only a certain number of rooms and beds available, not everyone who needs a place to live can get one immediately. When all beds are full, problems may arise.

“[TLP applicants must] wait from someone to get kicked out or wait for someone to graduate out of the program,” said Smith. ”Sometimes we are able to find some folks their own apartments if they are working a pretty good job.”

For students who are not yet 18, and are also unable to find residence within the TLP, options are limited.

“If you are under 18, you can’t go to the regular homeless shelter. In Iowa City, we lack housing options for students who, for whatever reason, can’t be at home. [We lack] someplace for them to stay,” Kahle said.

According to Smith, who is one of three people (two full-time) staffing the Transitional Living Program has been around for somewhere around 40 years now. Despite its longevity, many homeless and unaccompanied teens are still unaware of the resources available to them through TLP and other local lodging services.

“We [at the UAY], we’re pretty sure that there’s some individuals who don’t even know who we are [who are] dealing with these types of situations,” said Smith. “We want to figure out how we can get to those individuals because they need us. That’s what we’re here for.”

While she finds her work fulfilling, Smith tries to keep it separate from her personal life.

“One of the things I was taught a long time ago is that though we want to make an impact on everyone we come across, we can’t. We’re not going to be able to change the world with every single person.”

The silhouette of a school bag.

Educational Barriers

Teenagers with an inadequate or irregular housing situation also face hardships in enrolling, attending, and being successful in school. Other challenges might include absence of support from a caregiver and lack of basic needs, including food and medical care, resulting in hunger, fatigue, and poor health.

Not having fixed housing also makes it harder for teens to access legal and financial paperwork that someone in a more stable position would typically get from a parent. This can complicate otherwise simple tasks, such as filling out FAFSA forms to get federal aid for college, medical information, employment, obtaining government assistance, and more.

“If you are [a certified] unaccompanied youth, then you can click a box on the FAFSA and that just means you don’t have to give your parent’s information,” said Kahle. “That automatically makes you eligible for the full Pell Grant and as much loans and grants as you can get.”

Before being certified as unaccompanied youth or minor at the federal level, students must go through an interview process with a student family advocate (Kahle or Trefz) or City High’s Career Advisor, Russ Johnson.

“We kind of go through that, let you tell us your story, figure out where you’re living,” said Kahle. “In one way it’s totally black and white, because you have to be considered homeless under the McKinney-Vento Act and not living with a guardian, but it’s also not that easy. There’s a bunch of grey area there, so we just have to get as much information as possible so that we can make a judgement call.”

Outside of college admissions, homeless teens might also face several challenges getting through each school day.

“Constantly worrying about where you’re going to sleep at night [can affect academic performance],” said Kahle. “A lot of high school unaccompanied youth kind of couch-surf. Stay with people as long as they’ll let you, and then you find someone else and then you find someone else. Constantly having that worry–where I’m going to lay my head at night–is not a very good way to focus on your studies.”

Frequent school mobility, or changing between different schools often, has been linked to lower graduation rates, lower academic achievement, and higher dropout rates for students in transitional housing. The National Coalition for the Homeless reports that 75% of homeless or runaway youth have dropped out or will drop out of school.

As a result of these barriers, the McKinney-Vento Act strives to keep students in their original schools through the rights and resources it provides to homeless and unaccompanied youth, which, along with transportation and lunch services, also include FAFSA assistance and tutoring services.

In addition to implementing the provisions of McKinney-Vento, schools can support homeless teens in other ways. One way of doing so would be to make sure that teachers are cautious of their demands in the classroom, creating an environment which helps homeless and unaccompanied students feel welcomed. For example, when assigning homework or other classwork, teachers can take care to understand the barriers to completing it for homeless students, who may have trouble gaining access to Wi-Fi, taking photos, making food, or bringing in objects from home.

“Not having a place to plug in your Chromebook, or not having Wi-Fi where you’re staying…all of those things that most kids take for granted are things that unaccompanied youth constantly have to think about,” Kahle said.

*Names have been changed in order to protect the privacy of certain individuals.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Iowa City High School. For 2023, we are trying to update our video and photo studio, purchase new cameras and attend journalism conferences.

You drop your phone. Your heart stops. "Is my most loved device done for?" You wonder to yourself. As your arm feverishly and quietly stretches downward...

You drop your phone. Your heart stops. "Is my most loved device done for?" You wonder to yourself. As your arm feverishly and quietly stretches downward...