Little Women Makes Big Waves

January 30, 2020

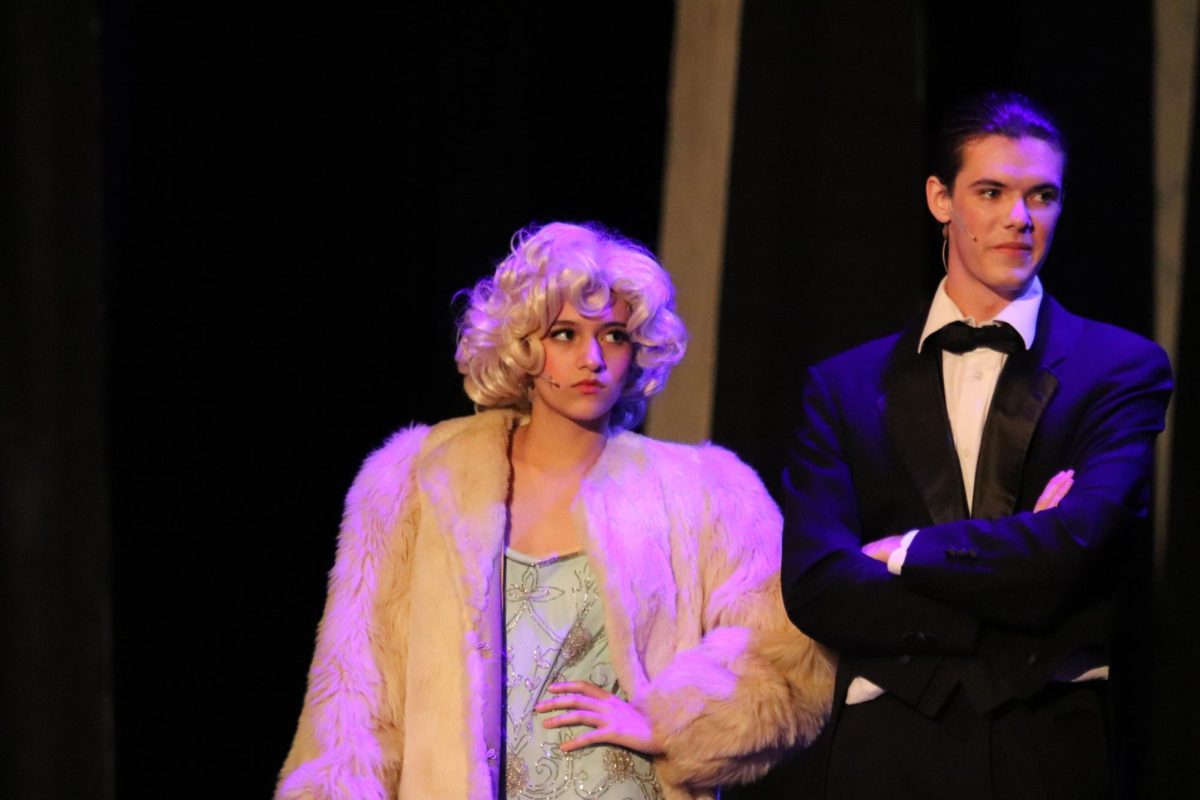

“Little Women” opens with Jo March (Saoirse Ronan) pausing outside of a door to pull her nerves together. Anyone familiar with Lousia May Alcott’s iconic character knows that Jo March is not known for her hesitancy. The cause for this uncharacteristic unease is revealed as she pulls open the door and weaves her way through a room filled with men. It’s a newsroom. She approaches an older, distinguished-looking man sitting at a desk and tells him that she’s here on behalf of a friend looking to sell a story to the magazine, although one look at her ink-stained fingers reveals herself as the true author. She doesn’t even get the dignity of a response as the man wordlessly takes her work and reads through it, carelessly crossing out pages of material as he goes.

Jo carefully masks her breaking heart each time his pen makes another slash on her paper and is on the verge of giving up hope when finally he replies that they will take it–with revisions, of course. She inquires about pay and he responds that they pay 25 to 30 dollars for work like hers; for her story they’ll pay her 20. Finally, on a leaving note, he tells her if she writes another story, to “make it short and spicy. And if the main character’s a girl make sure she’s married by the end. Or dead, either way.” Audience members sit unsurprised yet disgusted by this blatant sexism. Jo is ecstatic. Money in hand, she pulls up her skirts and sprints the whole way home.

Greta Gerwig, the film’s director and screenwriter, directs this scene as what it is–a fight scene, writing in the screenplay that Jo “exhales and prepares, her head bowed like a boxer about to go into the ring.” Life for a young woman in 1868 is only made more difficult by Jo’s aspirations of becoming a writer and her contempt for the societal expectation that women are only fit for marriage. Gerwig makes it clear from the beginning that Jo March will fight tooth and nail to gain as much respect in this world and patriarchal society as she can.

“Little Women” is a fantastic coming-of-age film that sheds light on the constraints of the time period that women faced and brings to life the story of four sisters growing up. There have been countless adaptations of this classic novel throughout the years but Gerwig’s surpasses them all, artfully weaving together the two books Alcott wrote about the the March family in 1868 and 1869. The first centers around the girls as children and teenagers and the second shows them as young women on the brink of marriage attempting to learn how to exist in adulthood. What sets Gerwig’s adaption apart from those that precede it is how she incorporates both stories, blending them together seamlessly, beginning with the story of them as adults and flashing back to their childhood. Because of this, the character development is portrayed realistically and incredibly. Meg (Emma Watson), the oldest, is responsible yet dramatic and takes it upon herself to keep Jo, the second oldest, in check. Jo in her 16 years has still not found a way to come to terms with the intense disappointment she felt to be born a girl. She can’t do half the things she wants, beginning with fighting in the war with her father. Amy (Florence Pugh), the youngest, is vain, a spoiled child who embraces and romanticizes the idea of marrying a rich man. Finally, there is Beth (Eliza Scanlen), the second youngest–and sweetest–child, who only wants good in the world and their father to come home safely from fighting.

The story pivots on the rivalry between Jo and Amy. Amy begins this story as a whiny child envying her older sister and everything she has, but unlike in adaptations that only include the first book, in Gerwig’s creation Amy’s character arc is done justice. Historically, Amy is portrayed as the unlikable March sister and the antithesis of Jo–shallow where Jo is deep and selfish where Jo is selfless. Gerwig’s version, however, challenges the rigid stereotypes about female likability seen so often in media and creates Amy as a fully formed character. Sure, she is, as many are, a flawed and insecure child and she romanticizes the lavish life that she will have when she follows the advice of her grandmother (Meryl Streep), and marries a rich man, but as she grows into adulthood she grows out of her childish outlook on life. While she still finds marrying a rich man alluring, the appeal no longer comes from a place of selfishness and instead is rooted in practicality: she wants to take care of her family. Marriage is, in her words, “an economic proposition” and she intends to play an unfair, undesirable system to her advantage to the best of her ability.

Through incredible directing, a star-studded cast, and artful filming, “Little Women” stays true to its historical roots while simultaneously being transformed to feel unreservedly modern. While the books are widely renowned classics, they are filled with long, winding, moralistic passages and don’t exactly appeal to all audiences, but unlike in the books, there’s not much moralizing in Gerwig’s adaptation…Oh, Mrs. March (Laura Dern) is almost cloyingly self-sacrificing, but the focus is primarily on the March sisters. Gerwig makes sure to show the complexity of their relationships with each other–their rivalry and jealousy, the fun and the fights–and this is what ultimately makes it such compelling viewing.