Awake and Aware: To Kill a Classic

We need to stop romanticizing Harper Lee’s classic and recognize it for what it really is.

In the wake of a school district in Biloxi, Mississippi removing To Kill A Mockingbird from an 8th-grade reading list, there has been a lot of talk (most of it critical) surrounding the decision. The part of the decision that seems to be receiving the most ridicule? A statement released by the vice president of the school board saying that the language used in the book made and makes people uncomfortable. According to the LA Times, the N-word is used nearly 50 times throughout the book. Despite this fact, supporters of Harper Lee’s notorious novel say that banning the book on the grounds of discomfort is insufficient. I would agree with this statement, considering the fact that any non-black person’s reaction to the use of the N-word will only ever stop at discomfort.

Non-black people will, fortunately, never have to experience the pain or the pressure that enters your chest whenever your entire race has been reduced to a single word. Banning the book on the grounds of discomfort is insufficient. Supporters argue that the use of the N-word is critical to achieving historic authenticity and to censor the book or its use in classroom discussions is counter-productive. However, removing the book from a reading list when it has so many anti-black messages in it that you must start to question the weight of its educational value? That just seems like common sense to me. If you’re asking whether or not I’m shocked that the black narrative has been completely removed from today’s conversation on Mockingbird, I would have to say no. Historically, blacks have always been silenced in the attempt to speak, express their views, and articulate their feelings, especially if accounts of their experiences make people uncomfortable.

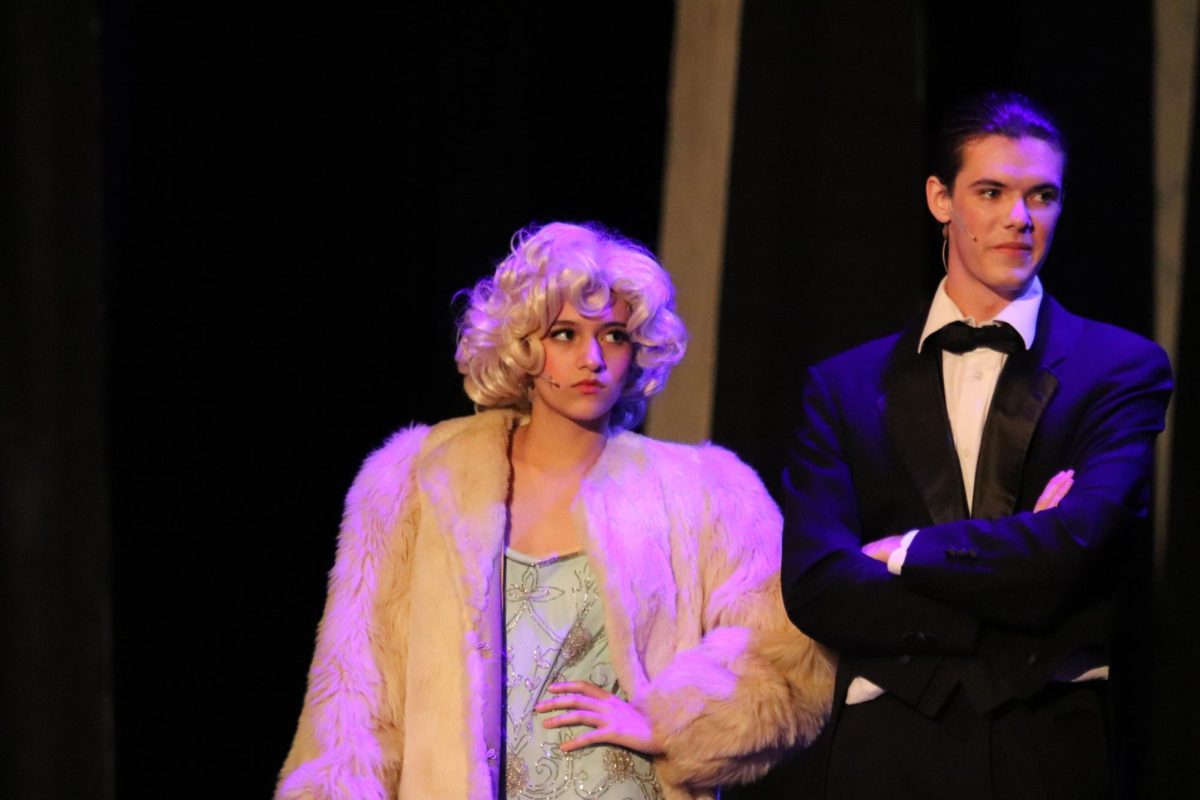

When we read To Kill a Mockingbird last year in Ms. Sotillo’s English class, I had mixed feelings. I was still sorting through my weighted opinion of the storyline and it felt hypocritical to openly speak out against the book when I was playing a small part in the City High production of the play. For one thing, there was all the talk heralding the show for having more diversity than past school productions have had. This didn’t quite sit right with me the first time I heard it and I later realized why.

Every black character in the story is written into a position of inferiority. Most or all of them were written using controlling images. Calpurnia is the Finch’s maid and a manifestation of the Mammy caricature; Tom Robinson is stripped of his masculinity and his humanity at the imagination of a white woman (and I don’t mean Mayella) as his family (of disposable characters), as well as black students, are forced to watch and endure from our very own classrooms. Over and over while being submerged in this storyline, the same thoughts kept running through my mind, Why am I in this show? Why are we so happy to be playing maids and puppets? Why do people like this so much?

Unfortunately, at the time, I didn’t have the language to express these thoughts and feelings. Now that I do, I feel obligated to do just that. Every black character in To Kill a Mockingbird is used to further the plots of the white characters. All of them lack depth or lives extricated from those of the white characters that they seem to orbit. We only ever get to know the black characters as they are viewed by the white characters within the story. These reckonings, coming from Harper Lee, a white woman who was raised in the South during the time in which her book is set, are inherently reductive of the black community. Tom Robinson never becomes a man in the eyes of the reader. He is only ever a negro to be pitied. When putting a face to the N-word, in their minds, most people would probably conjure up an image of good ol’ (Uncle?) Tom.

While plentiful, these are just a few examples of harmful depictions of blacks that can be pulled from Mockingbird. All of these points only serve to strengthen a case for removing this material from classrooms. These reductive depictions do not take into account the actual experiences of black folk, but rather encourage romantic and harmful thinking. Wherever To Kill a Mockingbird goes, pseudo-discussions on race follow. We end up with readers who seem to think that Racism is summed-up by an angry white man trying to get a black man convicted for a crime that he didn’t commit, the jury that couldn’t meet his eye, or even the president that their country elected. While these may be a few explicit examples of the products of Racism, these discussions disregard the larger oppressive structure. You get people that never realize how advocating for a book that is so clearly anti-black, even when a black person tells them so, is a product of Racism too.

Harper Lee didn’t have black people in mind when writing her novel. She was clearly envisioning a white audience. She was never advocating for black people, she was instead, trying to speak for us. In her mind we were nothing more than rabid dogs to be shot in the street, put out of our misery. Unless and until we can shift the way that we teach Lee’s book in classrooms, reshaping the romantic perception of it, and exposing it for what it really is: a mess of antiblackness, nothing good is actually being done by teaching this book. The amount of criticism that anyone who dares to speak out against the book for exemplifying the very discriminatory values that it supposedly condemns is an argument for its removal in and of itself.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Iowa City High School. For 2023, we are trying to update our video and photo studio, purchase new cameras and attend journalism conferences.

Olivia Lusala enjoys applying pigments to paper in a pleasing assortment of color. When she grows up she aims to have a kazoo solo on the Broadway stage....